(cognitivewonderland.substack.com)

My postdoc advisor always drank bad coffee—the stuff easily available in shared department kitchenettes. When a student in the lab tried to get him into good coffee, he responded that he actively didn’t want to develop a more mature taste in coffee.

The student thought this was irrational—surely, you’ll get more out of coffee if you learn what tastes good!

My advisor replied that it wasn’t irrational to have preferences around your own preferences—meta-preferences. He wanted to remain the kind of person that didn’t know what good coffee was.

This very brief interaction has stuck with me for years. We often say there’s no accounting for taste, indicating there’s no way for our base preferences to be irrational. But what about meta-preferences? It feels odd to say they can be as arbitrary as base preferences—with base preferences we know there is some (often impossible to know or articulate) evolutionary, physiological, or psychological story about why we like certain things. But surely we need some story to justify a meta-preference as well.

What might a rational justification be?

Naive theories of rationality leave out much of human psychology. But our preferences are all about human psychology. If we leave it out, what we’re left with isn’t a theory of human rationality. But the more of human psychology we try to account for, the broader our notion of rationality has to be—muddying distinction between rational and irrational.

It’s a common sentiment that lotteries are a tax on the mathematically challenged. Since lotteries (and roulette wheels, slot machines, etc.) make money for the state or company administering them, the expected value of a lottery ticket must be lower than the cost of the ticket.

If you pay more than the expected value for something, you are on average losing money. The occasional win at a slot machine is more than offset by how much you would have to pay to make it likely to win. Over enough pulls of the slot machine or enough lottery ticket purchases, you should expect to lose money.

This is also broadly true of things like insurance and warranties. Companies generally offer these because they make money off of them, meaning the expected value is below what they charge you. It seems Amazon now allows you to purchase warranties on even small electronics—but if you spend your life buying every warranty, even on cheap $15 mice, you’ll likely spend much more on warranties than you’ll save on replacements.

The common advice is to only insure big things that would be ruinous if you lost them without compensation—your house, car, or breadwinner would be examples.

But is it irrational to buy lottery tickets, or play a roulette wheel, or buy insurance on something you could replace without financial ruin?

A naive definition of rationality might be “optimizing the average amount of money your decisions make”. But by this definition, we’re all irrational.

Think about how much you would like a billion dollars. Probably quite a lot! It would make an enormous change to your life. But what about two billion dollars? You might prefer that to one billion, but realistically, you don’t value it twice as much as the first billion. The first billion is a major life change that allows you to live an unfathomably luxurious life. The second billion is just a cherry on top.

If you were trying to optimize expected value, you would prefer a 51% chance of $2,000,000,000 to a 100% chance of $1,000,000,000. But my guess is you would prefer the sure billion dollars to slightly better than a coin flip for 2 billion.

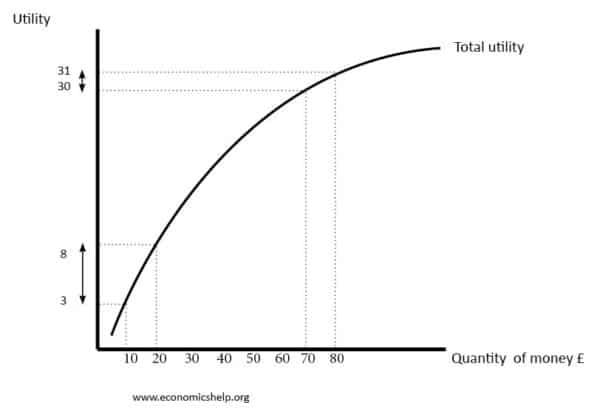

Money has what economists call diminishing marginal utility—the more you have, the less the next dollar is subjectively worth to you.

Most things in life have this sort of diminishing returns. One piece of cake might be great, but what are you even going to do with ten?

The concept of utility is meant to capture how much things actually matter to you. The objective amount of money might double, but the amount you value it won’t. It’s clear that any theory of rationality needs to take into account how much we subjectively value something.

Instead of it being irrational to choose something that lowers your expected monetary value, we can instead say it’s irrational to choose something that lowers your expected utility. We preserve the place of subjective preferences and allow for things like declining marginal utility.

Note, though, that this actually makes playing the lottery more irrational. If money has diminishing returns, it makes even less sense to pay a small amount that’s more than the expected value for a possibly large payout.

But, by opening the door to subjective, psychological factors like utility, we’ve actually opened a different defense of the rationality of playing the lottery.

Saying that playing the lottery is irrational because the expected value is lower than the price assumes that all of the value is in the outcome. There’s something external that you want, and gaining that thing is what has value to you.

But a common defense of playing the lottery is that it allows you to fantasize about winning—you’re paying for the chance to daydream, not the expected value. If there’s no accounting for taste, then surely it’s fine for us to place value on something like fantasizing about a possible future.

This idea conflicts with a standard model in economic decision-making, though.

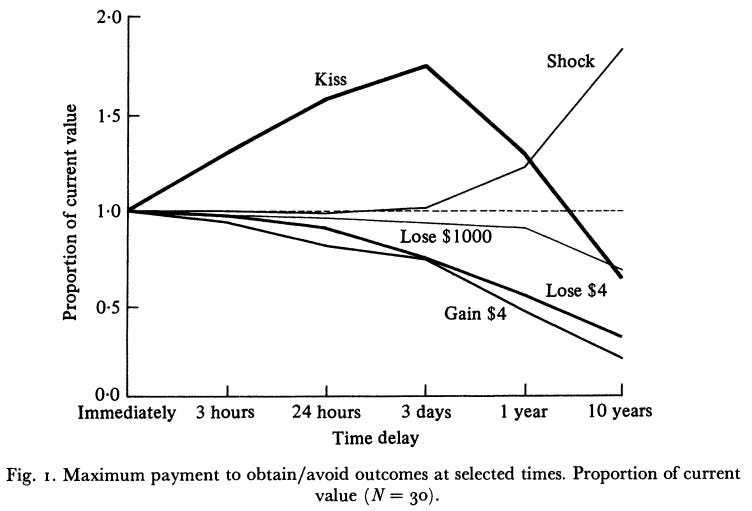

It’s common for models of decision-making to assume that the further an event is in the future, the less it’s worth to us. According to delay discounting, you might prefer $50 now to $60 in a year.

There are all kinds of perfectly rational reasons you might have this preference—maybe you are worried about the risks of what might happen over the next year (I might not have the money to pay you, we both might forget I owe you $60, and so on). Or maybe you have an immediate desire for something that requires $50.

It’s hard to claim that wanting the $50 now is irrational. But it certainly would seem irrational to say you prefer $50 in a year to $60 now. If I give you $60 now, you could just put $50 in a safe place and have it in a year, and use the extra $10 to do whatever you want!

But there’s again a problem of trying to generalize from maximizing money to maximizing utility. There are plenty of cases where it is perfectly reasonable to want to delay getting something we value.

A classic paper surveyed students on the value they would place on getting to kiss the movie star of their choice at different times—either immediately, or sometime in the future. Participants valued delaying the kiss—just for a few days. If delayed too much (10 years), the kiss lost some of its value.

The reason is simple—getting to anticipate the kiss for a few days has value. There is utility in anticipation.

What of our daydreaming lottery players? You could make the case that they are being irrational—after all, they could fantasize about being rich without playing the lotto, and they would get to keep their money. But this is a weirdly robotic way of thinking about the issue—having a small chance that an outcome will actually happen affects our attention. It makes it more believable.

Is it rational to pay for a daydream? You could say it’s irrational, because we could just do it. If you get value out of daydreaming about being rich, just daydream about being rich, you don’t need some insignificant chance of it actually happening to do that. But we don’t have perfect control over our attention—so unless you want to include “perfect attentional control” as part of rationality, it seems difficult to object to spending money to draw it towards something pleasant.

Let’s go back to the conversation I opened this article with: Is it irrational to avoid developing a taste for good coffee?

On the one hand, it can’t be—there’s nothing wrong with having a preference for a preference. There’s no accounting for taste, after all.

On the other hand, it feels like the preference needs some kind of justification. If I refused to learn what foods I like from a free cafeteria at work, and day after day ate stuff I hate and missed eating the stuff I like, and there wasn’t any reason for this (e.g. I’m not trying to lose weight or eat specific healthy things), you would be right to think I’m an idiot.

I think there are different mental models contributing to this tension. If you think of learning to appreciate coffee as revealing preferences I already have, it seems irrational not to learn about coffee and reveal my taste for it. It’s like failing a learning task—something that psychologists have robust models of rationality around. In this view, a preference not to learn good coffee is just a preference not to do the things that would bring me value, and it seems appropriate to call that irrational.

But this is leaving out the psychological context of what it means to get into coffee, just like calling someone irrational for taking actions that don’t maximize their financial gain leaves out utility and other psychological factors.

It’s easy to think of reasons why you might prefer not to develop a taste for coffee. The most obvious is you don’t want to be a coffee snob. If you just don’t like the vibes of people who like fancy coffee, that’s reason enough to not develop a taste for it.

It also could be that you know you’ll rarely get to drink the good coffee, so even though the taste of the good coffee itself will be of higher utility, knowing what your drinking is bad will produce regret that you’re not drinking better coffee. You’ll be lowering the utility of the coffee-drinking experience you have most often.

The model that leads you to call this meta-preference irrational leaves out plausible psychological factors for why you might prefer to not develop a taste in coffee.

But once we allow for these sorts of “non-consumptive” values—values driven by things internal to us, like what we pay attention to—it becomes much more difficult for a theory of rationality to have much normative force. It seems there is always a way to justify things—even things many of us would consider unreasonable, like spending months in the freezing cold, exhausted, with a chance of losing fingers.

One of my all-time favorite behavioral economics articles is George Loewenstein’s paper on the utility of mountaineering, titled “Because it is there“. Loewenstein is interested in mountaineering because it’s so different from the usual cases that decision-theorists and economists consider. It isn’t about money or the consumption of some external good, has extreme downsides, and yet people do it.

Mountaineering isn’t about pleasure. In fact, it’s miserable. Extreme mountaineering can involve frost bite, loss of extremities, and even death. You spend months going hungry, being exhausted, and levels of discomfort that are hard to fathom from the comfort of a couch. Loewenstein quotes a mountaineer, Joe Simpson, who had to drag himself out of a crevasse he had fallen into and across an ice field, all with a broken leg:

however painful readers may think our experiences were, for me this book still falls short of articulating just how dreadful were some of those lonely days. I simply could not find the words to express the utter desolation of the experience.

Through this hardship, most aspects of mountaineering are just drudgery. One foot in front of the other, where the climbers have to come up with ways of distracting themselves and keeping their exhausted mind occupied. For example, Mike Stroud (also quoted in the Loewenstein paper) says:

I occupied my head with inanities. This consisted chiefly of silly songs, such as “The Teddy Bear’s Picnic”.

Given how miserable mountaineering sounds, why do people do it? And why do they do it over and over again?

Loewenstein gives a few different answers, each corresponding to a different category of “non-consumptive” value:

Self signaling: the only way to prove to yourself you have some feature—courage, grit, fortitude—is to see how you deal with such extremes. The pain and misery are inseparable from the signal you send.

Goal completion: doing something damn hard, knowing how hard it is.

Mastery and control: the ability to show you have the skills to master the harsh environment.

Meaning: Many mountaineers, especially after close calls, come back with a different perspective on life—going so long, often months, without the usual comforts and without family or usual activities gives a different perspective and appreciation of those things.

But Loewenstein also points out how bad people are at describing why they put themselves through such things. For example, the mountaineer George Mallory, when asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, responded “Because it is there.” (This is where Loewenstein gets the title for his article).

People can’t necessarily articulate why they go about doing the things they do, which makes the whole messy business of trying to figure out if someone’s behaving rationally or not even harder.

There are canonical examples of irrational preferences—for example, if you prefer A to B, and B to C, you better also prefer A to C. Otherwise your preferences are intransitive and someone could turn you into a “money pump“:

Suppose that you start with A. Then you should be willing to trade A for C and then C for B. But then, once you have B, you are offered a trade back to A for a small cost. Since you prefer A to B, you pay the small sum to trade from B to A. But now you have been turned into a money pump. You are back to the alternative you started with but with less money.

But outside of these toy examples (and even within them), the line between rationality and irrationality gets messy.

You can try to define rationality as maximizing expected value, but the “value” we are maximizing is hard to capture. If you define it as money, we’re all irrational. If you define it in terms of external things, we ignore the rich psychological motivations we have for many of our most important actions.

Once we take into account psychological reality—that what our attention is on, self-signalling, meaning, and so on—it’s hard to tell the difference between irrationality and a complex utility function.

Revealed preference theory makes this problem salient: it defines preferences based on what you choose. A drug addict who continues to take a drug, by definition, prefers the drug—even if they say they want off of it.

This is, I submit, not the most useful way of looking at drug addiction (or weight-loss, or procrastination, etc.). It dissolves the notion of internal conflict and the messiness of human reasoning. Without a normative theory of how we should act, we lose the ability to improve our actions.

What counts as “rational” depends on what work we want the concept to do. If we’re looking at a money-making machine, we might only care about expected monetary value. But if we’re trying to understand—and help—humans, then we have to include messy details of psychology.

Normative frameworks might never capture the full complexity of human psychology. There are enough degrees of freedom that it’s hard to ever know for sure any action is strictly irrational. But maybe that’s okay—maybe the point of these frameworks is to give us tools for thinking and to improve our own reasoning about our preferences, rather than some ultimate arbiter of what is or is not rational.

So go ahead and keep drinking bad coffee, unless all this talk of utility functions has you second-guessing it.

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button below if you enjoyed this post, it helps others find this article.

📚 Join the Cognitive Wonderland book club to read and discuss cool books on science and philosophy with us. 📚

If you’re a Substack writer and have been enjoying Cognitive Wonderland, consider adding it to your recommendations. I really appreciate the support.