(blog.jacobstechtavern.com)

If you’ve been living under a rock for a year, I have shocking news about the election*, and great news about the future of Swift portability.

Swift for Android is here.

More specifically, a quite early-days developer preview is here.

This tool is in its infancy, but formalises over a decade of homegrown toolchain hacks used by cross-platform wonks to enable Android to talk to Swift code.

As it happens, I’ve got a touch of experience using Kotlin Multiplatform, a.k.a. KMP. It’s always been the most palatable cross-platform solution for native mobile devs, since it works by sharing business logic in a cross-platform module, but allowing for fully native iOS and Android UI code.

I figured, let’s get ahead of the debate/war your iOS and Android teams are inevitably going to have and compare the developer experience of both cross-platform tools.

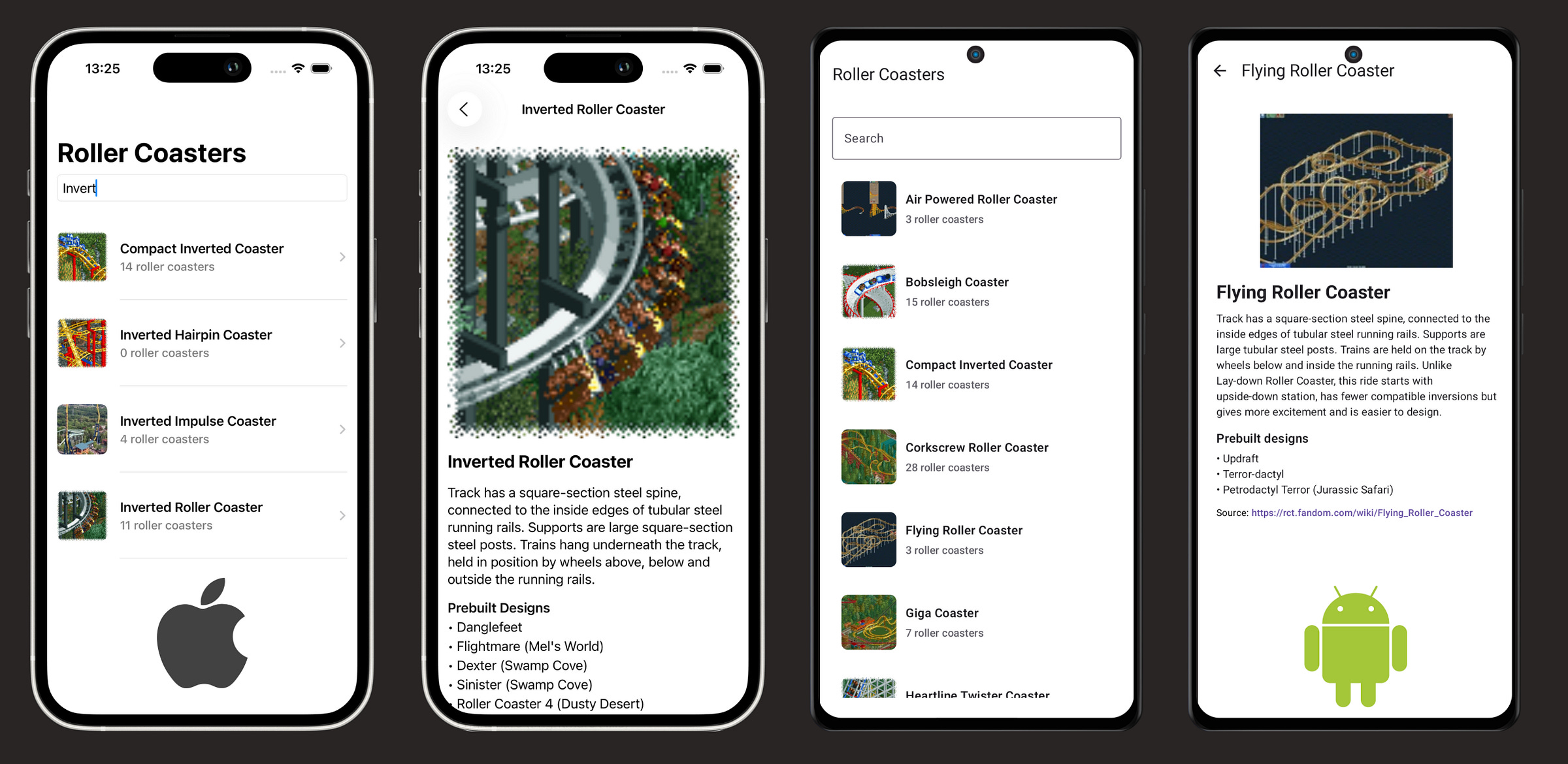

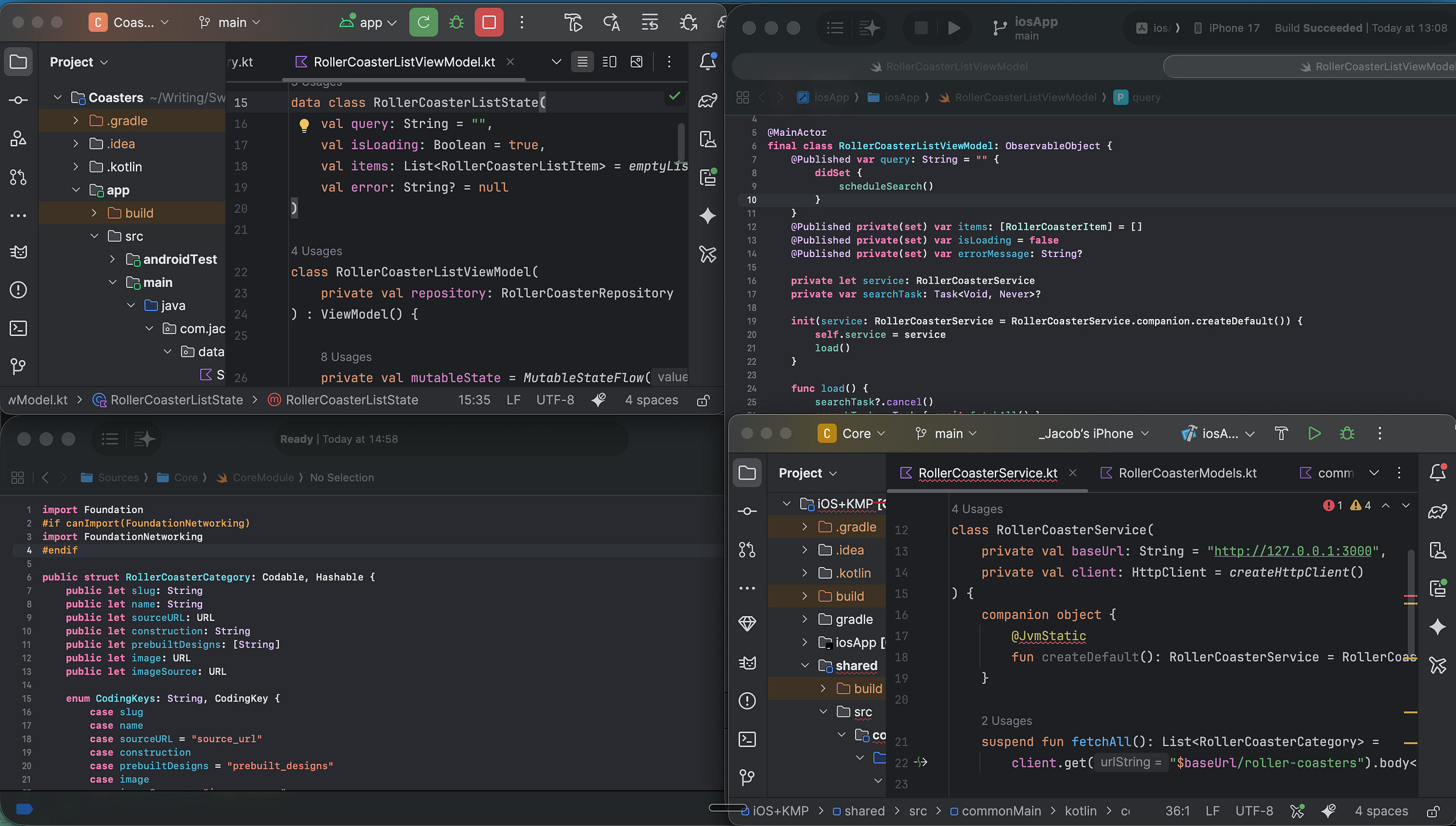

Now that I have nothing better to do with my time, I spent the week playing with Swift for Android, and KMP, setting up a pair of cross-platform apps based on Rollercoaster Tycoon 2. Swift for Android powers the Android app (with Jetpack Compose), and KMP powers the iOS app (with SwiftUI).

Here’s what I learned.

*I didn’t say which election, please project your biases favourably

I open-sourced both projects. If you want to start your own Swift for Android project (or KMP for that matter), you can fork it to use my project as a baseline:

https://github.com/jacobsapps/SwiftAndroid-vs-KMP

Subscribe to Jacob’s Tech Tavern for free to get ludicrously in-depth articles on concurrency, SwiftUI, iOS performance, and Swift internals in your inbox every week.

I’m not going to be a jerk about it, because Swift for Android is brand-new and not released for production. The big announcement was to declare the existence of nightly builds for the dev preview.

It’s been built by Swift and Android toolchain gods who have spent a long time doing it the Hard Way™, and I can only assume the new tooling is an enormous improvement on what was possible before.

But… it might need a couple more months in the oven before I can recommend refactoring your production app. Things are moving fast, though: I had to rebuild my sample app the morning I published this because they added async-await compatibility.

In a sane world, this article would be 80% me whinging about the setup experience, but I’m a professional, so I’ll try to cap it to 25% at most.

I’m going to do something weird and put a nice code comparison at the beginning, so all the iOS developers can look at the Kotlin and think “boy, am I glad I don’t have to write that”, and everyone who’s an Android developer can look at the Swift and think “ew, who would want to write that on Android”.

My sample apps have 5 cross-cutting components.

A simple ExpressJS server that serves a JSON API over localhost

A Swift package that fetches data from the network and decodes it into data models. Network requests returning models are exposed via a public service.

Android app that calls into the Core Swift module, queries the service for rollercoaster data, then displays it on a list.

The KMP twin brother of Android+Swift/Core. Also fetches data from the network and serialises it into data models, exposing a public service.

iOS app which calls into the shared KMP module, queries the service for rollercoaster data, then displays it on a list.

Let’s look at how the code differs between the two languages.

Let’s start by looking at some Swift code we’ll use in Android, then some Kotlin code we’ll use on iOS. We’ll dip our toes into data model setup, then look at how to implement networking via cross-platform service injections.

Swift data models use Codable to automatically parse out JSON data into a struct, a value type useful for simple data transfer.

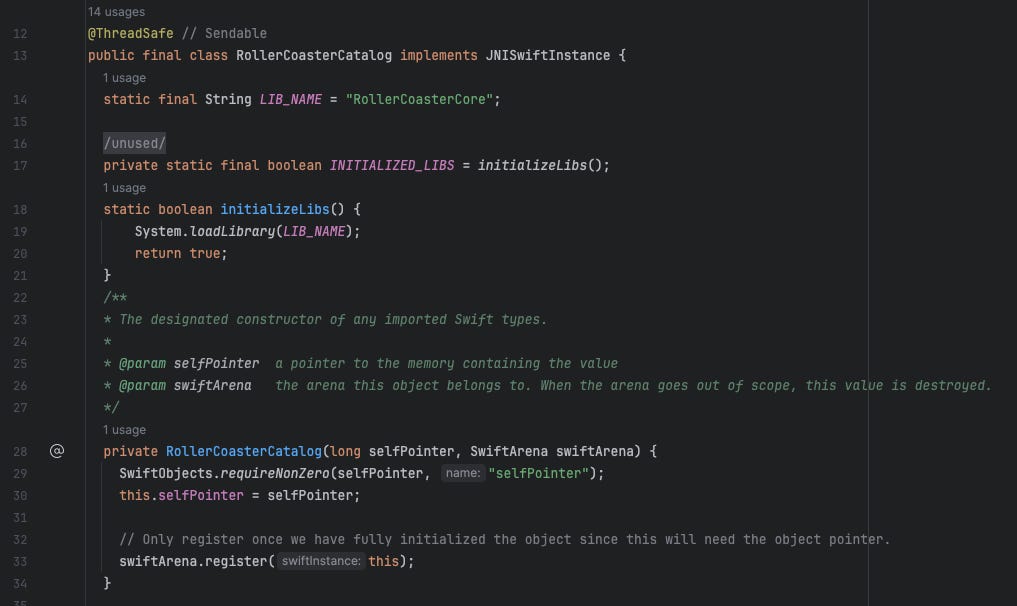

Android apps call into Swift code via JNI bindings generated from our code using swift-java. JNI, or Java Native Interface, allows Java code running on the JVM to talk to other languages. swift-java is the interoperability layer that creates Java interfaces from our Swift module code (we’ll look at these soon), allowing it to be compiled as a native Android library.

Marshalling arrays and handling Foundation types like URLs across the module boundary can be brittle and error-prone, so I created some simple bridging code to expose primitive-typed getters for Foundation types like URL and implementing array indexing.

Please avoid looking through my commit history to see how I landed here: my first iteration literally yeeted the JSON string across the module boundary. I expect before Swift for Android becomes Production Ready™, there will be a simpler, idiomatic way to pass things like arrays across the module boundary.

Kotlin stores data in a data class, a reference type for which Kotlin synthesises a bunch of value-like behaviour for copying, equality, and printing.

It uses a @Serializable data class to store data, which basically works just like Codable. If you’re used to the giant umbrella module that is Foundation, it might look strange to individually import every package like kotlinx.serialization.Serializable, but this is how pretty much every ecosystem outside iOS does it (the IDE automates it).

Now that we’re sufficiently warmed up, the networking logic begins to get interesting.

The Swift code looks like run-of-the-mill networking code, except for the imports.

This conditional import block is required on non-Darwin platforms.

#if canImport(FoundationNetworking)

import FoundationNetworking

#endifThis imports the open-source, cross-platform, Swift re-implementation of Foundation’s network libraries to allow the basic Foundation APIs like URLSession to work on other platforms*.

*This is explained really well in Pierluigi Cifani’s excellent talk, Android Doesn’t Deserve Swift—But We Did It Anyway.

If you want to go deeper on swift-foundation, you can also check out my recent work:

The KMP project uses idiomatic Kotlin libraries like Ktor’s HttpClient to perform network requests asynchronously using a suspend fun.

Kotlin Multiplatform has a very neat way of neatly injecting platform-specific code. First, you declare a provider file with an expect fun.

Now the actual fun begins. For each platform you’re implementing on, you set up the expect fun’s implementation: “actual fun”. Here, we can inject Ktor’s built-in HTTP client for Darwin platforms.

It’s also possible to eschew the expect/actual pattern, and use a pure DI approach: Kotlin interface with implementation object injected into the KMP side from native code.

I’m not sure there’s a way to achieve the same using Swift for Android. I expect platform-specific implementations, plus the accompanying ergonomics, will come as the platform evolves. You can already do a lot using the vanilla swift-foundation frameworks, and 25% of the Swift Package Index has already been cross-compiled to work on Android, so I reckon we should be okay for now.

I’ve shown you how you can write data models, networking, and simple business logic in your preferred language. It’s an amazing leap that we can now call into multiplatform code from an app using the platform’s native UI language.

But this boundary between native and cross-platform code is where everything can fall over.

If the cross-platform library has rough edges, devs are gonna get cut. 🩸

My simple rollercoaster project on Android uses a cookie-cutter Repository pattern, along with Coroutines, to call into our Swift library code.

Once we’ve successfully compiled our Swift package as an Android library (using some arcane Gradle incantations, more on this later), we can import the package like any other Android module.

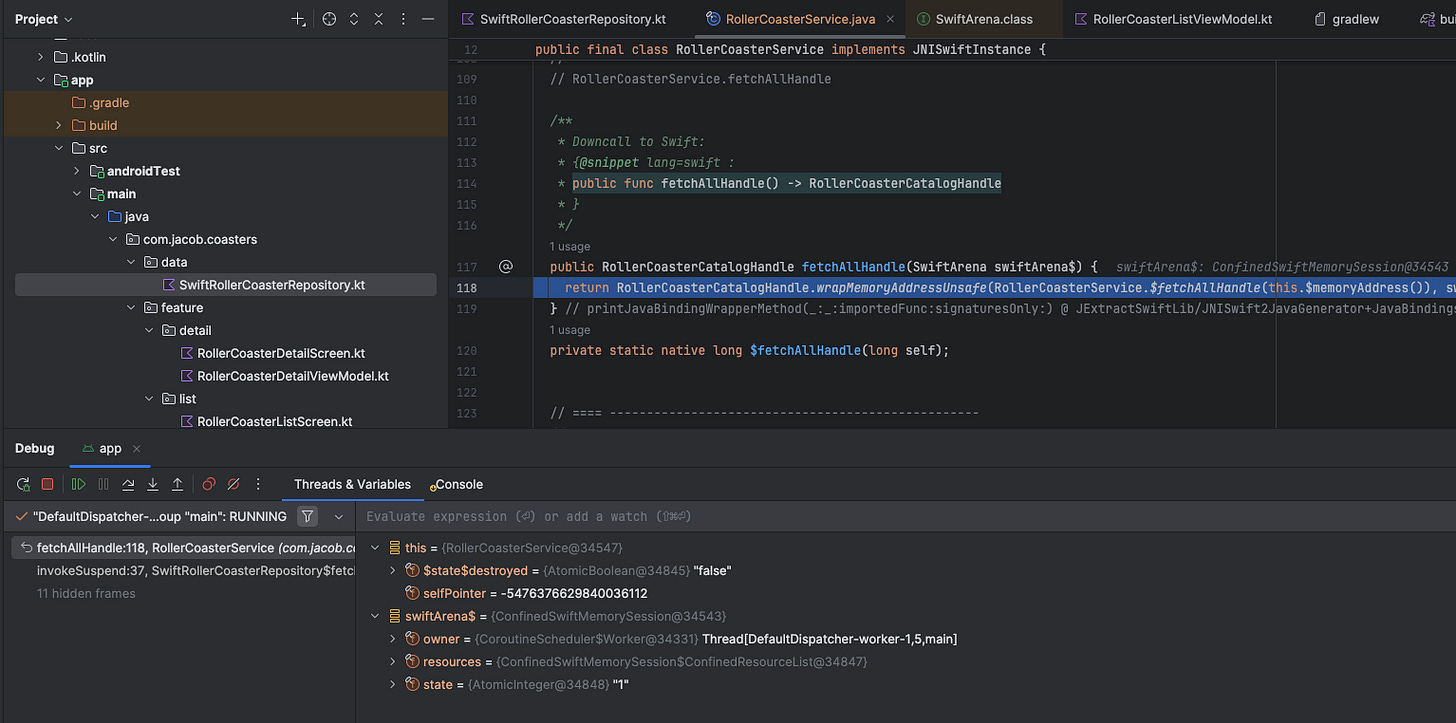

import com.jacob.core.RollerCoasterServiceThe networking service is instantiated using SwiftArena, a part of swift-java. SwiftArena basically manages the lifetime of Swift objects on the JVM. Think of it kind of like an @autoreleasepool.

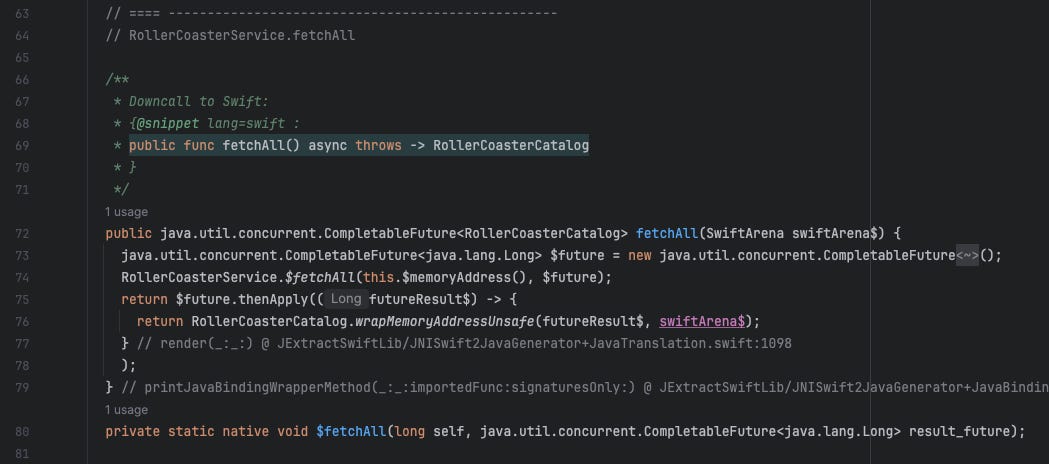

Our fetchAll() method calls straight into the service’s interface, which fetches and returns our data models. The Swift async/await interface is converted into a CompletableFuture in the JNI bindings. We call the getter methods on our model object to convert it into native Kotlin objects for use in our UI layer.

If we CMD+Click into the model, we can see the Java interface that’s created when swift-java builds the Swift code as an Android module:

Here we can see the java.util.concurrent.CompletableFuture created from our async Swift interface that allows the asynchronous operations to interoperate.

Let me clarify something though (or, more specifically, Pierluigi Cifani clarified it on his proofread. Thanks!)

The Swift code we call into is compiled Swift code, running on the Swift runtime. The interface here is just the binding that allows it to be called from Android’s JVM. Objects in our Swift code, like our service, can be referenced from inside the JVM, and SwiftArena helps to manage memory at this boundary.

Idiomatically, the KMP shared library is called “Common”. Or, sometimes, “Shared”. You can modularise the library as much as you like, but you will need to expose this to the platform apps as a single umbrella framework. This is pretty annoying for namespacing, but you stop noticing it pretty fast*.

*Alex Bush told me, actually, there’s a beta of Swift Export for KMP that resolved the umbrella framework issue, allowing multiple modules to be used from KMP in iOS.

We perform JSON mapping here to give our SwiftUI view a nice value type to work with, but it’s not mandatory in this case. Using DTOs is a very common practice when working across module boundaries, even outside of cross-platform apps.

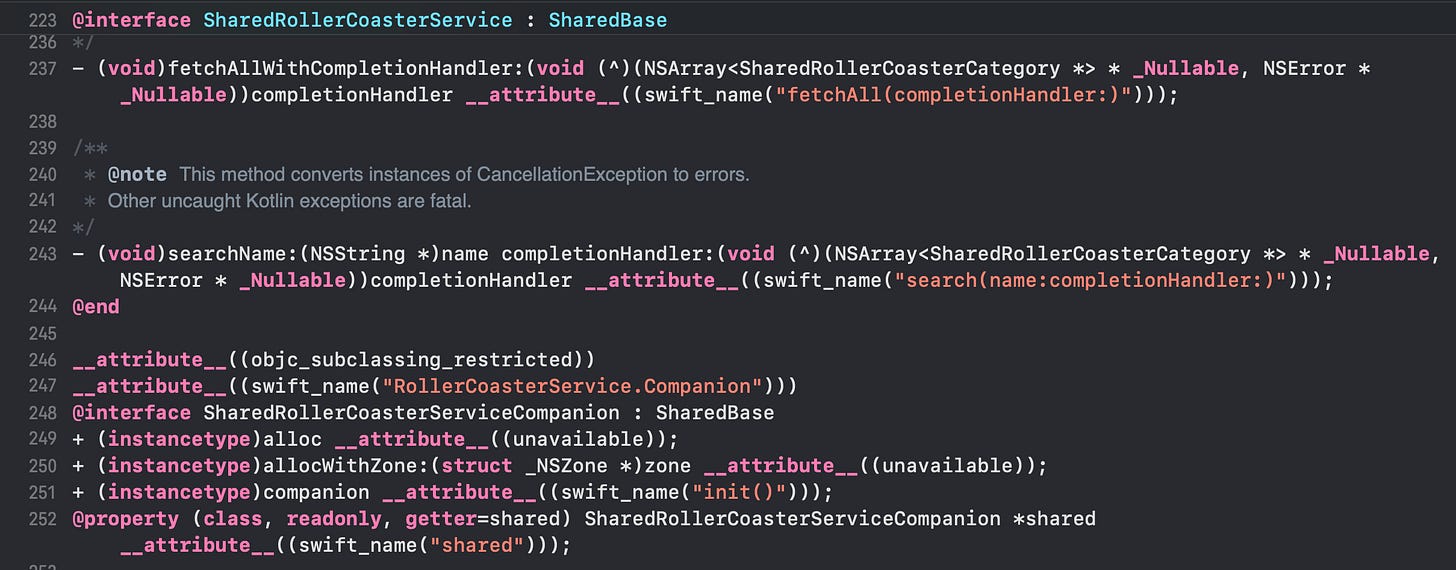

Let’s CMD+Click into one of the Shared functions:

Here we see the inner guts of how KMP works: it generates Objective-C headers for all your Kotlin code.

This is actually why KMP has existed since 2017, whereas we only just got around to Swift for Android in late 2025. When Kotlin compiles into machine code, its compiler is able to generate Objective-C headers for this code, and Swift was built from day 1 to be compatible with Objective-C.

The Swift for Android team had a hell of a job cut out for them going the other way around: there was no JVM-compatible toolchain just lying around, and no convenient compatibility layer, so they had to hack it together from scratch.

When you’re running a long-term KMP project, you might want to use SKIE (Swift Kotlin Interface Enhancer). There’s a few rough edges around things like suspend functions, interfaces, and sealed classes which the library sands down into idiomatic Swift signatures. Other projects might want to manually implement wrappers around the KMP interface, converting Coroutines to things like Combine publishers, RxSwift observables, or AsyncStreams.

Building multiplatform libraries can introduce friction, and never more so than when you want to test your code. Sure, the unit testing experience is pretty fine when working with a simple module, but what if you want to test against your real APIs?

The lack of a UI you can plug into can be frustrating, especially if you’re building business logic separately from the UI code.

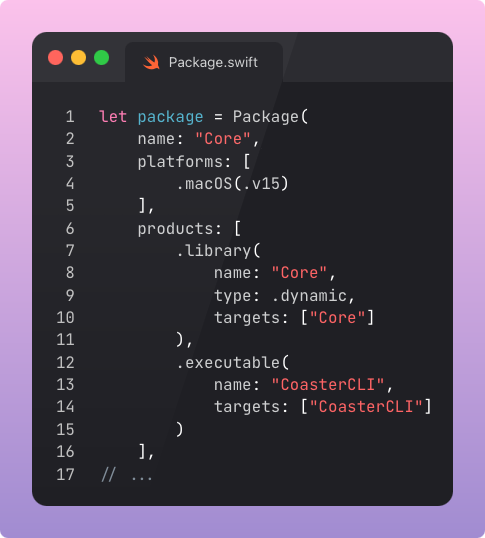

To improve quality-of-life for my team, I like to build a little CLI app target on top of each multiplatform module to get around this limitation. It imports the multiplatform library and allows you to interact with it via a simple terminal-based call-and-response command prompt.

The Package.swift here is straightforward, with a new binary executable.

If you don’t want to introduce target overload across your modules, you can also suck it up and write unit and integration tests across your codebase. It’s the business logic, so you have no excuse!

Interlude: What were they thinking?

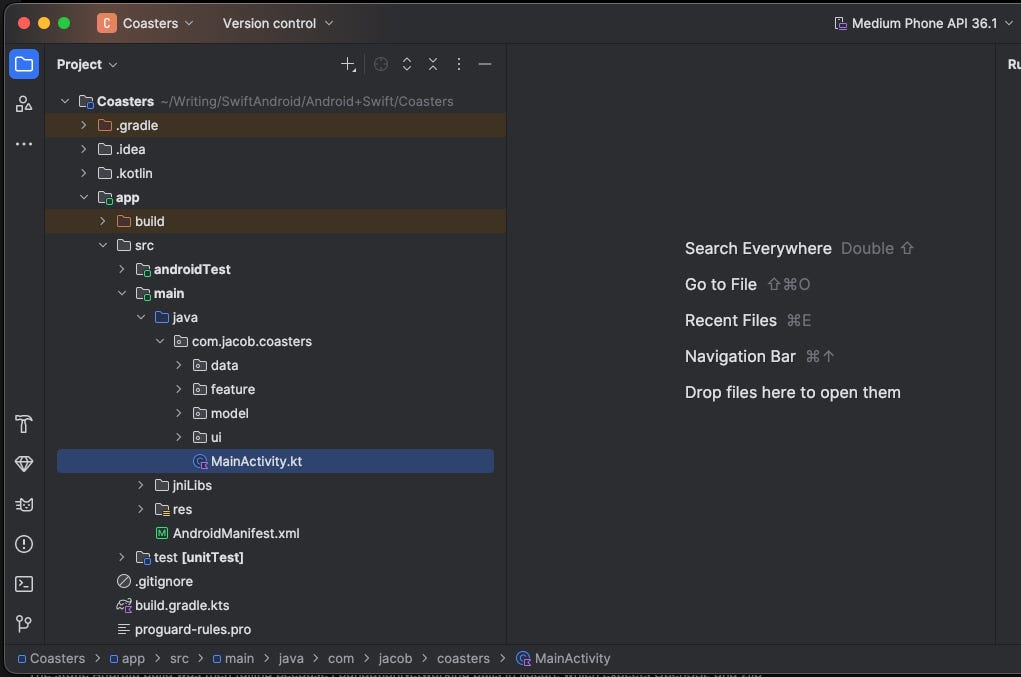

I don’t want to re-litigate my teenagehood with the whole “PS3 vs Xbox 360” debate again, but the default folder structure for Android code is bananas. You’ve gotta go 7 levels down to get to the default MainActivity!

*Ahem*, okay, got that out of my system. Onwards and upwards.

This is the single most controversial point of debate when implementing a multiplatform solution. Where do we put the view models?

*I guess nowadays it’ll be a distant second, after “Are we using Kotlin or Swift?”

“Shared business logic” unambiguously includes networking, caching, analytics, models, processing, queues, config, and most of your services.

But view models (and, depending on your architecture, perhaps interactors, presenters, and navigators) could go either way.

This is a double-edged sword.

If you put all these in the shared multiplatform libraries, you’ll potentially increase the percentage of shared code from ~50% to ~80%.

But, if you choose to share these, you’re also going to be fighting (at least) one of the systems at some point. SwiftUI expects @Observable view models. Jetpack Compose prefers StateFlows.

If you go down this route, you’ll go insane unless you use some kind of wrapper library like KMP-ObservableViewModel as a shim to make code work on the non-native platform. I have absolutely no clue about the performance implications of this, other than that it’s not zero.

I made life easier for myself and kept the view models on the native side.

It took me a while to name this section, but I think I hit the nail on the head. I doubt “the big IDE crapfest” would sufficiently convey the overwhelming mental overhead that comes with bouncing between 2 instances of Android Studio (or IntelliJ) and 2 instances of Xcode, for 2 different implementations of the same project.

From my experience, IDEs are the roughest ongoing edge in the multiplatform world. You’ll inevitably have to context-switch between IDEs to find the code you’re looking for at the shared module boundary. You can’t even CMD+Click to jump to function definitions: you’ll land in the confusing hellscape of synthesised ObjC/JNI bindings.

You have a couple of not-great solutions to this.

First, do everything in Visual Studio. This makes context switching between projects less jarring, but sucks a lot because you lose everything that makes your IDE useful. You still mostly need to manually search for function definitions.

You can also write most of your code using an agentic AI CLI, but this kind of delays the inevitable. You’re going to need to debug inside the IDE eventually, and the context switch is even more dramatic. What’s worse, dorks on the internet will judge you for using LLM tools.

In the real world, I’ve seen KMP shops employ a novel org structure: “core engineers” vs “design engineers”. One team that writes business logic, and another team that focus 100% on UI code. Compared to the standard “one dev per screen”, this requires careful coordination on API contracts, and falls over if your requirements are subject to change.

I didn’t really know where to put this callout, but it’s kind of important.

Mobile apps live quite high up on the abstraction pyramid, atop innumerable system frameworks, the operating system, and hardware.

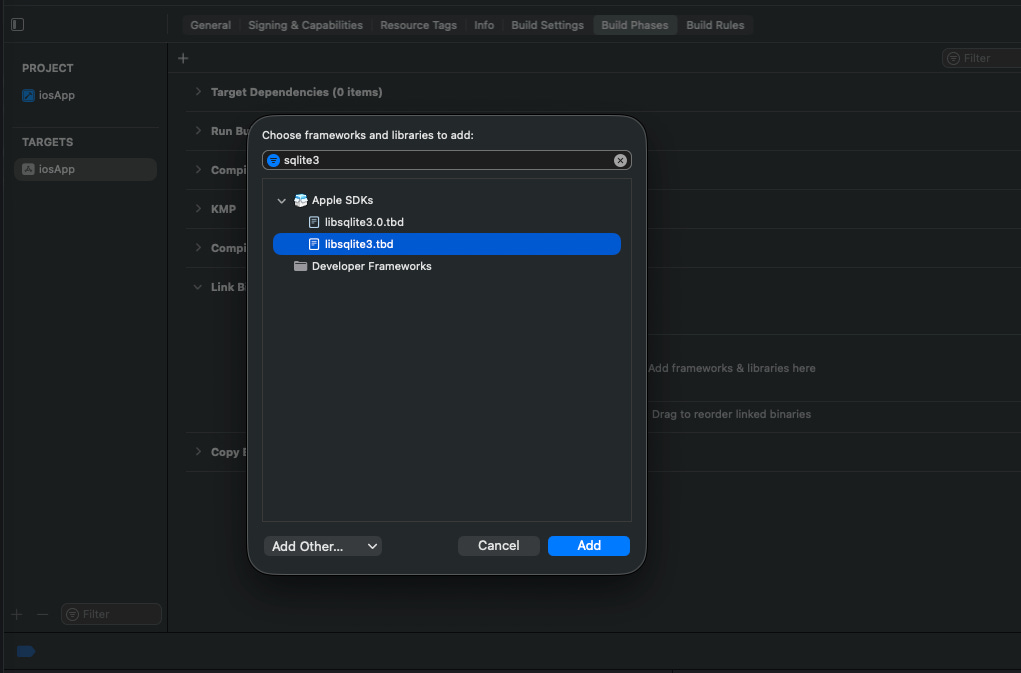

Many popular libraries, such as Ktor’s HttpClient or the SQLDelight storage client, require a system plugin to connect to the underlying native drivers. In the case of HttpClient, it’s the relevant device networking daemons, and in the case of Room, it’s the system’s underlying implementation of SQLite.

Therefore, for KMP apps, you often need to manually link native iOS system frameworks to get these libraries behaving correctly.

On the Swift for Android side, URLSession on Android builds atop curl and zlib, but it looks like FoundationNetworking handles these sub-dependencies handily.

You’ll probably get similar multiplatform friction when it comes to cryptography, keychains, notifications, haptics, location services, file system, camera hardware, background execution, and more. Multiplatform brings a nice shared API for your business logic, but isn’t a free lunch.

This is kind of where React Native and Flutter start to shine in comparison: by necessity, they ship with unified bridging wrappers to directly interface with all these across both iOS and Android.

I promised at the beginning I’d try not to whinge about this too much. And you’re in luck: In the two days that elapsed between setting up Swift for Android and writing this up, I’ve successfully managed to repress the memories.

There’s a few steps to setting up the basic KMP app.

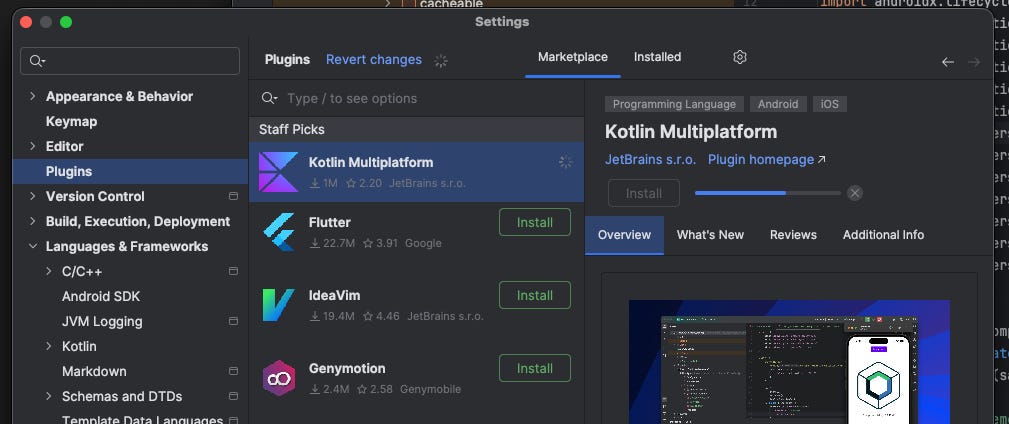

Install Android Studio, then install the KMP plugin.

File > New > New Project > Kotlin Multiplatform.

A ton of files and projects are created: shared, iOSApp, and composeApp.

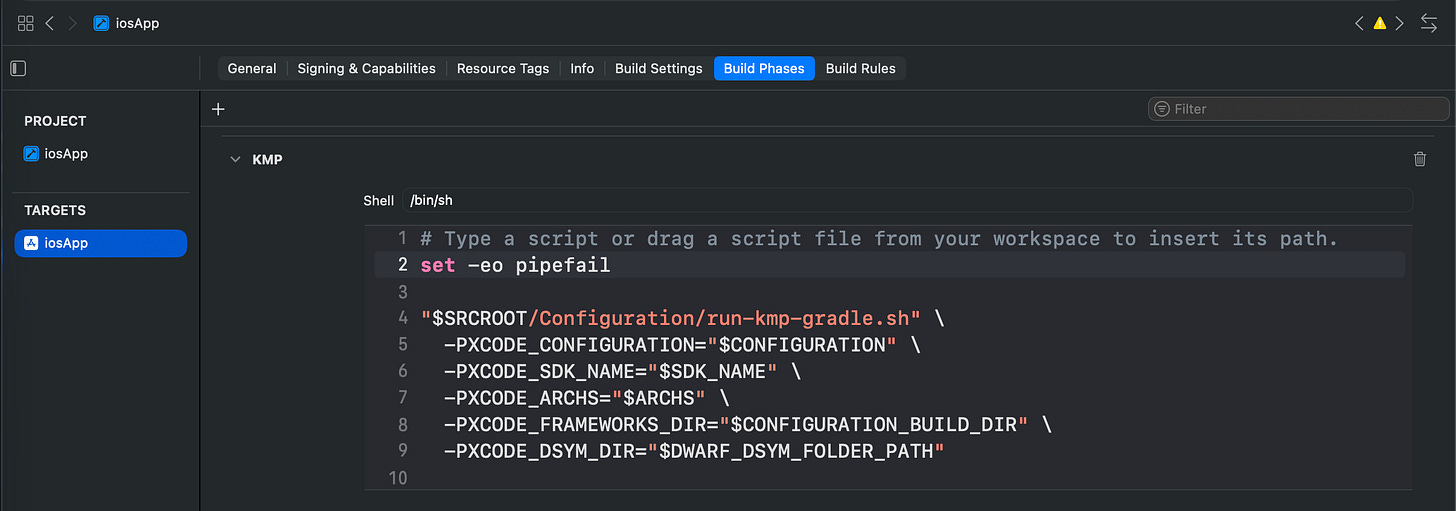

The main rough edge is the build script you need to add into Xcode, or the code won’t compile.

Also, nobody explains this, but you also need to have the right Java/JDK version setup somewhere or nothing will work and you won’t know why.

That didn’t feel great. But in time, you’ll remember even this moment with fondness. KMP is pretty mature and well-documented in comparison to what comes next.

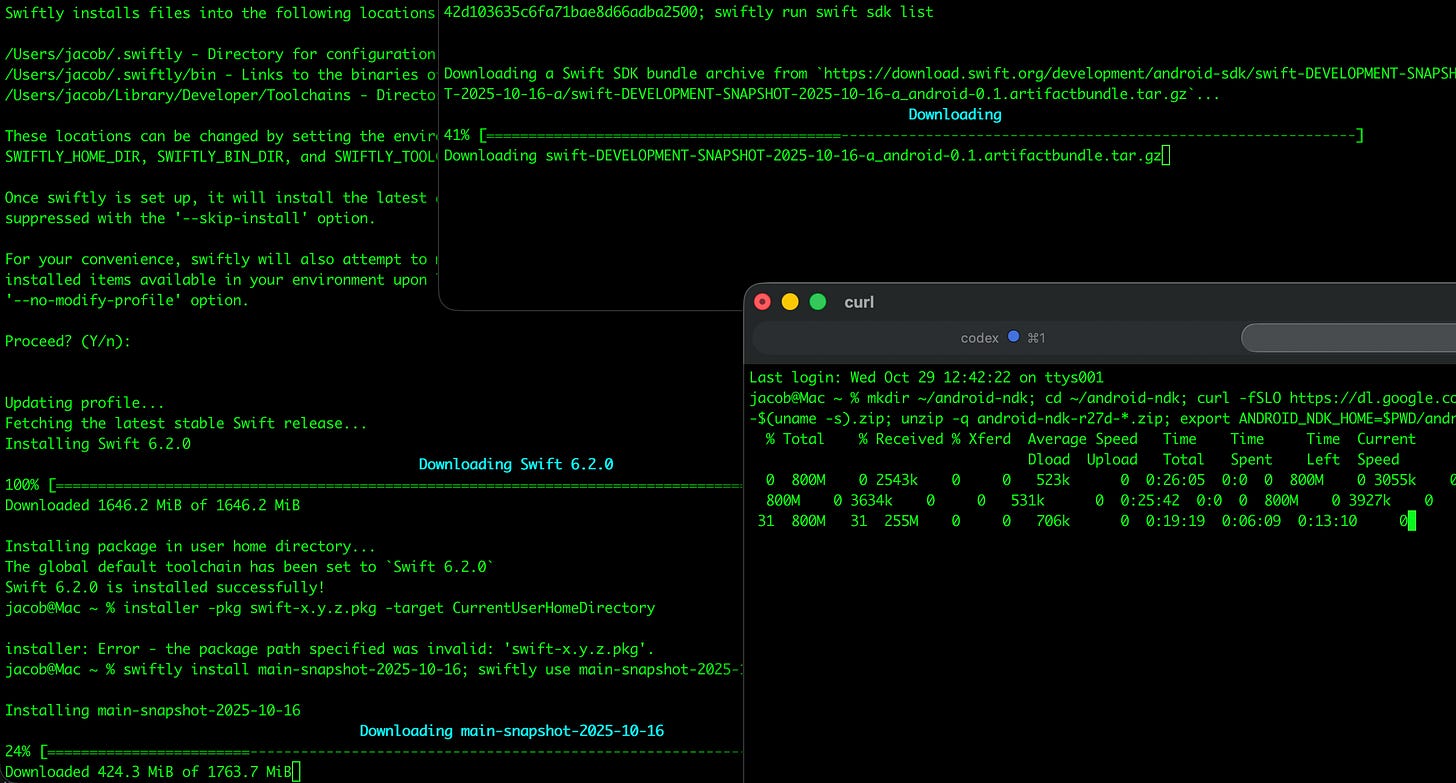

As mentioned, I sort of blocked most of this out, but it was something like…

Downloading specific version numbers for 3 different toolchains, including the Swift 6.3-dev branch:

Downloading the JDK so you can actually build stuff to run on the JVM. Aim for version 21, or bad things will happen. I followed the documentation, like a moron, and landed on version 25, which is incompatible with Kotlin and Gradle.

There is a vast chasm of missing steps between the Getting Started Guide and the swift-android-examples, exacerbated by the fact that it doesn’t look like there are currently any full Android app projects in the examples.

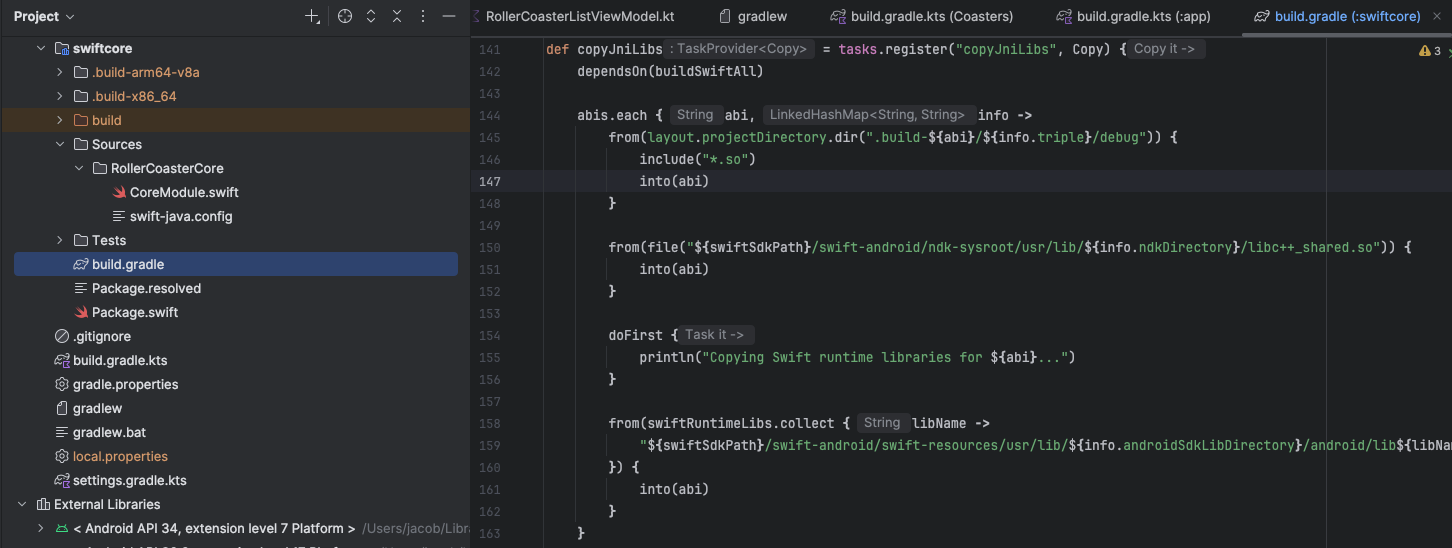

I don’t know if I’m doing something really dumb, but the only way I could get anything to work in a proper Android project was by copy-pasting my Core code into the Android project (swiftcore) and setting up some ludicrously complex plumbing in the associated Gradle build script.

The build script hooked into the Android project’s pre-build step. It cross-compiles the Swift package for each Android ABI into fresh .so binaries and copies them into the Android project’s jniLibs folder, and generates JNI stubs in the build folder.

In addition to this, I copied a bunch of the Java system pathing workarounds from the example projects into my Package.swift in order to get anywhere.

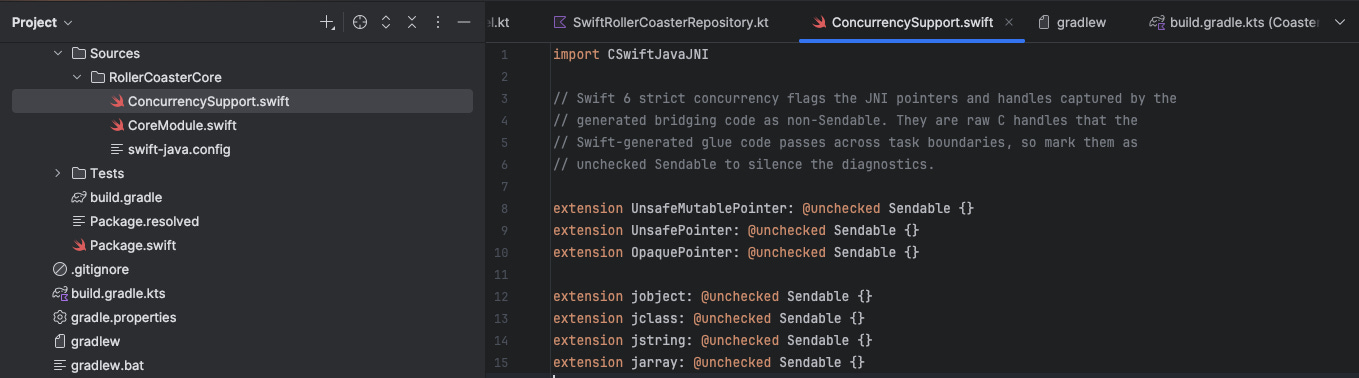

…plus, to get the concurrency interop over the line, I had to add a few shims.

Like I said, it’s clear the Swift for Android toolset was built by people for whom writing 209 lines of toolchain plumbing is easier than breathing. I expect the tooling will rapidly catch up to KMP, and you’ll likely be able to just whack out a single terminal command to set up a full working Android/iOS project with a common Swift core.

I should probably mention debugging a little. It’s not good. There’s always going to be a rough edge whenever you’re jumping between IDEs.

In KMP, Android devs are first-class citizens. You can jump between breakpoints into the shared code and step through logic. On iOS, it’s a bit sucky. You can technically set breakpoints in the generated ObjC, but it doesn’t work very well and the stack traces won’t be that straightforward.

It's the opposite on Swift for Android.

Swift for Android is essentially a compilation toolchain, so you can step into your Swift package as normal when debugging on iOS. But from Android code, your wellies will step straight into the cowpat of synthesised Java bindings.

We’ve learned what you already knew about debugging multiplatform code: every time you add a platform, you’re increasing the number of things that can go wrong. When you get trapped in the crevice between language boundaries, you’d better be an expert at both.

Every native mobile dev, in their heart, knows that the “business logic core, native UI” approach undertaken by Swift for Android and KMP is the superior approach for cross-platform compared to the all-or-nothing, look-the-UI-looked-fine-on-my-device approach from Flutter and React Native.

Swift for Android is new, shiny, raw, and teeming with rough edges. The main takeaway I can share is to give it a few months before you make the call to fire half of your Android team.

Kotlin Multiplatform is a little bit annoying to use from the iOS side, particularly when jumping between IDEs or debugging, but it’s well-documented, mature, and relatively painless with the right setup.

But it had an 8-year headstart.

The enthusiasm and effort pushing Swift for Android forwards is palpable. They’re improving the onboarding. They want to trivialise the build experience. The Skip Tools guy is part of the workgroup.

The original draft for this post used a pretty nasty synchronous, blocking URLSession call on the Swift for Android side. The morning of publication, I found a 3-day-old PR that supported async methods on Android, so I rebuilt the whole app to apply it.

Swift for Android’s SDK let me ship a Jetpack Compose app backed by Swift code. KMP let me ship a SwiftUI app backed by Kotlin. I have aged 20 years in the last week*.

*Though, to be fair, this was mostly from the daydrinking.

Both tools introduce a sharp module boundary where platform glue, debugging, and context switching will ensure the developer experience is never quite as good as pure-native. I know my fellow Xbox 360 owners won’t want to hear this, but the red ring of death is too much. If you have to go multiplatform today, stick to KMP. But this is subject to change. I kept it out of scope for this article, but if you want to ship something yesterday, I hear Skip greatly simplifies installation and usage.

I’m going to give it a few months and revisit once the Swift for Android SDK stabilises, then I’ll refactor my based 2FA app, porting it over to multiplatform.

As always, feel free to check out my open-source project and try out the tooling for yourself!

Thanks to Alex Bush and Pierluigi Cifani for proofreading and helping me avoid saying anything really dumb about KMP (Alex) and Swift for Android (Pierluigi) 🫡