(open.substack.com)

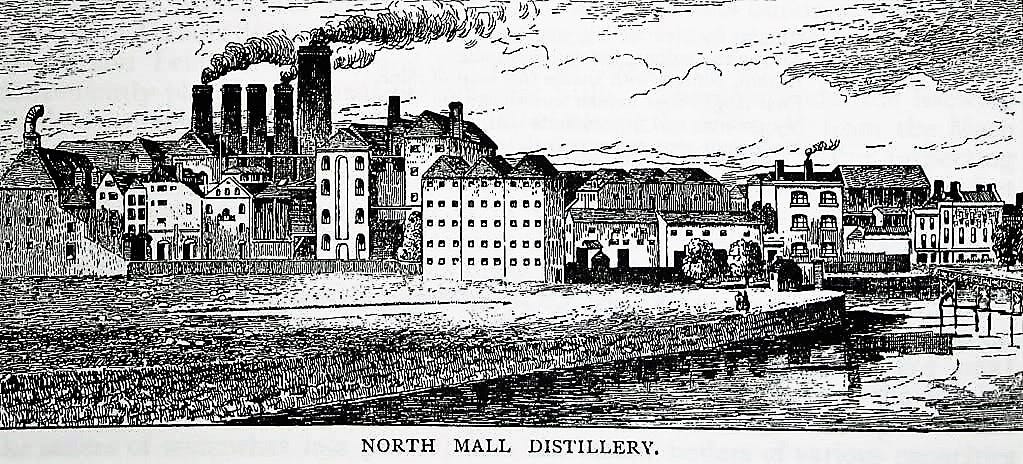

The distillation and consumption of spirits has been a pivotal Irish concern for centuries. Whiskey, from the Irish uisce beatha, meaning water of life, has served at the heart of these efforts. First consumed on the island in the 12th century, Irish whiskey is one of the oldest distilled drinks in Europe, and was once the most consumed spirit in the world. Whilst the industry would decline at the end of the 19th century, it has witnessed a return to international prominence. It is thus important that we seek to unearth the rich and winding story that underpins the industries modern success. Cork’s North Mall Distillery offers an excellent place to begin. Largely forgotten, this plant was once at the heart of Ireland’s whiskey story, and its echoes protrude well into the present day.

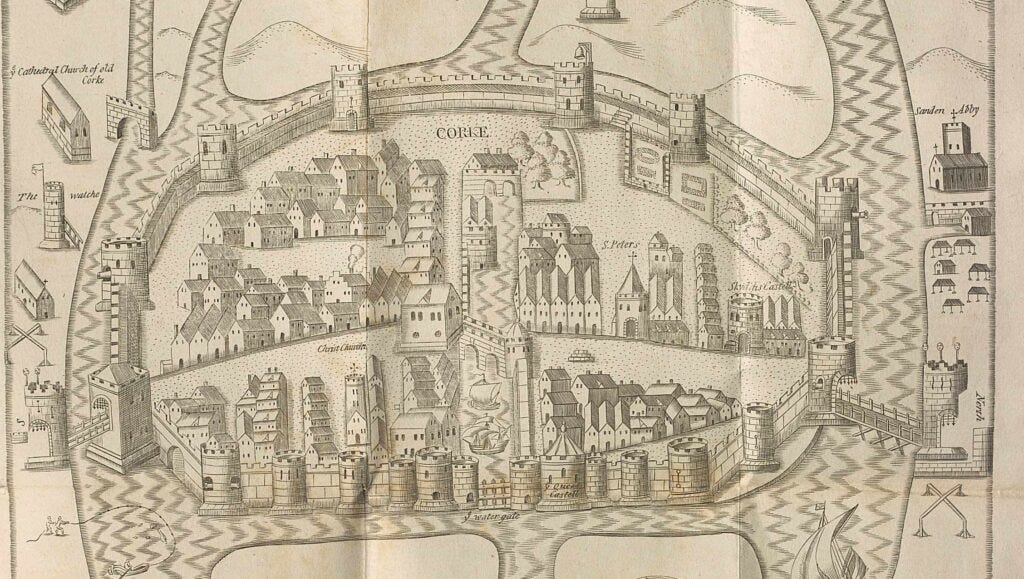

The site of the North Mall Distillery complex was originally owned by the Friars of St Francis Abbey. The founding of the abbey is dated to roughly between 1214 and 1240. Its explicit history is largely opaque, but a rough sketch can be taken from the historical record. Its location can be found on the above map, nestled in the right corner and labelled Sanden Abby. Its appearance here signifies its importance to the city.

The friary was most likely founded by Diarmaid MacCarthy Mór, King of Desmond, in 1229. According to a later source writing in 1540, it would be the first convent in Ireland to be suppressed during the Protestant Reformation. The buildings of the friary began to fall into disrepair by 1566. The Friars would return and build a new, smaller, church on the site in 1609. This church would be destroyed in the 1690 siege of the city. Bishop Downes would make the following observations during his 1700 visit to the site:

St Francis Abbey, on the north side of the Lee in the north suburbs of Cork. The site of it contains a few gardens on the side of the hill near the abbey. It is the estate of the Lord Orrery, before the late troubles held and inhabited by Mr. Rogers, Thomas Cooke and others. In King James’s time a new chapel was built by the Friars on part of the abbey, but not where the former chapel stood, some Friars living there. In the time of the siege the abbey with the rest of the suburbs was burnt. A good strong steeple remains standing. The chapel that was lately built, having been burnt with the abbey, was repaired by Mr. Morrison, a merchant, and is now used by him as a warehouse.

The gardens being referred to here are likely the future location of the distillery. It would be established on the main sloping ground west of where the abbey once stood. When works were being done to expand the distillery in 1804, several ancient coffins were unearthed, as detailed in the following 1852 account:

On excavating foundations of present buildings several stone coffins were discovered… The red stone rock which rises perpendicularly at the back of the buildings had on ledges at various heights coffins cut out of the solid stone, and the lid fitting so closely that to the casual observer it would appear to be part of the original rock.

An ancient well known as Tubir Brenoke, later called Tubbar-na-Brinnah and Tubbar vrian oge (probably, the well of learning or eloquence), which was mentioned as an early boundary in Philip Prendergast’s grant to the Franciscan Friars, was located by the foot of Wise’s Hill. This structure dates to the priory, and was considered so sacred that it attracted visitors from across the island. An entrance gate to allow people to access the well was located on the distillery’s eastern boundary wall.

It wasn’t long until the Wise’s were forced to shut up the well in 1810. This followed several incidents where individuals were found returning with pails of whiskey, rather than water. To mark its previous location, William Wise placed a carved stone into the store wall on the western side of the hill. The stone had been discovered nearby, and was likely part of some structure built on the grounds of the abbey following its dissolution. It remains in the wall today. Tubbar-na-Brinnah was not the only well on the friary grounds, with another located on the site of the modern Franciscan Well pub. This particular well can be visited within the pub grounds today if you book a tour through their website.

The precise nature of the founding of the North Mall Distillery had been clouded in mystery for some time. However, the work of Barry Crocket and Stephen D’Alton has shown, with reasonable certainty, that the business was most likely established by brothers William and Thomas Wise in or around 1798. Details are limited about this early phase of the operation, but evidence suggests that the business was founded on a strong commercial footing. It was operating at similar levels to the city’s other distilleries, with investment scaling up over time.

In 1802 a 1,112 gallon still (the primary apparatus used to make whiskey) was being used at the North Mall. By 1807 the Wise brothers had invested in a further 1,516 gallon still to supplement their manufacture. The precise nature of their ownership of the grounds of the distillery does not become clear until 1804. It is clear, however, that the business had been operating for some time prior to these arrangements. This is evident in the official records. What the distillery looked like in this early phase is not adequately recorded.

From 1804 the brothers had signed the official lease for the grounds of the distillery. The site was naturally advantageous, with Wise’s concern being the only distillery in Cork that drew its water-power directly from the north channel of the Lee. The companies watermill would be one of the last remaining structures of the distillery to survive, and was not torn down until the 1980s, making way for the then IDA Enterprise Centre.

By 1810 the distillery was a key player in Cork, being ranked among the four chief distilleries in the city. It was in this period that Thomas Wise granted a lease to his brother William for the plot of ground where the business bordered the North Mall. It was here William constructed North Mall House, known today as Distillery House. The structure consists of a fine Georgian townhouse with stables to the rear. Its usage has varied with time, yet it continues to stand in its full splendour today, offering the best preserved link between the area and its history.

William Wise had constructed his own home on the North Mall some ten years earlier in 1800. The building’s bowed design and height stick out strongly from the rest of the terrace, making for a more lavish design than its immediate context. This showcasing of wealth would lead to an attracting of criminality. William Wise would be robbed in 1836, but a far more remarkable incident would occur in the following year, as reported in the Kilkenny Moderator. It is worth reading the particulars:

At ten o’clock in the morning, a person of gentlemanly appearance, respectably dressed, and apparently of middle-age, went to the residence of Wm. Wise, esq., on the North Mall, knocked on the door, and handed a letter to the servant, to be conveyed to her master. This letter, which was signed ‘William Lander’, requested a private interview with Mr. Wise, as the letter had some important business to transact, and, on perusing it, Mr. Wise desired the servant show him up. Mr. Wise was confined to his bed, and on entering the room in which he lay, the applicant closed and locked the door, walked over to the bed, took a pistol from his pocket, raised the pan and examined the priming, and then with his left hand drew from another pocket a folded paper, open, however, at one end. The end he exhibited to Mr. Wise, and presenting the pistol at his head, he said, ‘Sign your name to this, or you are a dead man.’ Mr. Wise asked what it was? He replied, ‘I won’t tell you, but sign it at the peril of your life.’

Wise offered to sign a blank cheque for the man, but the intruder was insistent on having his own document signed. Wise ultimately did so, although not in his usual signature.

When his object was accomplished, the person who presented the paper, took it over to the fire and held it to dry, examining it deliberately two or three times during the process and all the while remaining with his face turned toward Mr Wise, and his eyes firmly on him. This occupied about a minute and a half. He then (putting the pistol on half cock) returned to the bed and said, ‘So far I have accomplished what I wanted. I have now but to say that if you attempt to make the least noise, or give the least alarm, until I am out of the house, though I should be at the hall door, I will return and blow your brains out.’

The individual subsequently left, with Wise summoning the authorities and giving information about the man. A letter arrived several days later from a ‘John Leader’, containing the signature Wise had written. It said that the writer ‘begged to return Mr. Wise’s signature as he had no longer occasion for it, the matter for which it was obtained, together with the signature of his relative, having been amicably arranged.’ The letter concluded assuring Mr. Wise that the writer was ‘very much obliged for the signature, and would have the pleasure of waiting on him had he not been under the necessity of leaving town, but that on his return he should have the honour of paying his respects, when he hoped to find him and Mrs. Wise in perfect health.’

The distillery continued on successful footing throughout this time, yet, like many early industrial pursuits, the business would become victim of fire in January 1820. Smoke and fumes began pouring from the coal store, and quickly hundreds of labourers worked to move the fuel, thought to be about 32,000 barrels worth. Unexpected coal fires were a common feature in large manufacturing concerns, and typically took days to bring under control, given the nature of the material. The fire would continue on, and an eyewitness account gives a sense of the scene:

I went to-day to see what progress they had made in taking away the coal which has not been as yet touched by the fire, and was completely awe-struck at the dreadful appearance of the place; immense volume of smoke issuing from every aperture. Numbers of men employed in throwing the half-burnt coal into cars waiting for the purpose-water falling from the engines as well as from a small stream, whose course they had turned into the stores, the flame occasionally bursting out almost under the feet of the men who were removing the coal, and all this under immense arches, over which were corn stores; and to crown the whole, the darkness of the place, which was only occasionally removed by the flame of the coal burning-altogether seemed to answer the description in Mythology of Tartarus, the residence of Cyclops.

The fire would be subdued by the 27th January, saving the distillery from total destruction. The cause was found to be the presence of a chemical compound in the coal that lent itself to combustion under storage conditions. It would not be the distillery’s last brush with fire, nor its most enduring.

With the risk of total destruction averted, the distillery got rapidly back up to speed. Industrialisation of the distillery carried on swiftly with investment in newer and larger stills. By 1827 the North Mall Distillery would surpass the production of Hewitt’s, the largest local competitor, with demand in the Irish market surging so dramatically that Irish distillers struggled to export any of their product abroad.

In 1828, the output of the North Mall Distillery would exceed that of the Dublin distilleries of James Jameson, John Power, John Jameson and Roe & Meyler. Only the Limerick giants of Stein & Brown would exceed the Cork plant. In the following year, Wise’s would produce 20 per cent more spirits than its closest competitor in Cork, totalling some 403,890 gallons.

During the 1830s, Cork would provide the largest market for spirits in the United Kingdom, producing some 20 per cent of the entire output of Ireland. The Wises would see stiff competition in the early years, but this would subside around 1834, leaving their North Mall Distillery sitting firmly at the top of the market. This surge in output in Cork is described in Samuel Lewis’ Topographical Dictionary of Ireland:

There are seven distilleries in the city and its vicinity; those in the former produce annually 1,400,000 gallons of whiskey, and in the latter, 600,000; the whole consume 268,000 barrels of corn, and employ about 1,000 men: the quantity of whiskey shipped at the port in 1835 was 1,279 puncheons [equivalent to 107,000 gallons].

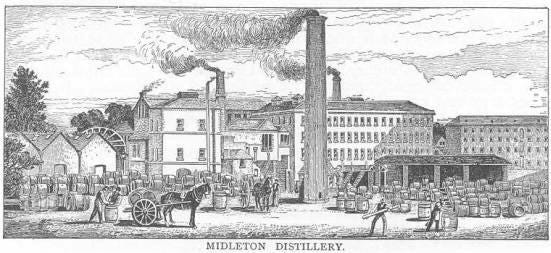

By this time James Murphy’s new Midleton Distillery had become a key player, sitting squarely among the top three distilleries in the region. This success was a product not solely of investment, but in refinements to the art of distillation. Strict competition, whilst pushing a downwards pressure on prices, also incentivised the creation of a better quality product. The whiskey of the early 19th century would bear very little resemblance to the product enjoyed today. It is thanks to the innovations of the 19th and 20th century’s that the product has taken on its modern, more palatable, character.

The mid 19th century would see a decline in the demand for spirits. This was due to three core reasons: population decline resulting from An Gorta Mór; Father Mathew’s temperance campaign; greater consumption of beer and stout. John Windele provides a rather humorous sense of loss here in his 1849 Historical and Descriptive Notices of the City of Cork:

There are within the City and vicinity, six distilleries which produced, before the going forth of the Missionary of Temperance, on an annual average, about two millions of gallons of whiskey, estimated the best in the universe.

Breweries began exiting the market, although most would return with a strengthening of conditions through 1850, where output began to increase again. The strong reserves of the Wise family would see them survive the worst of the downturn. Even so, the success of James Murphy’s Midleton concern was such that it would surpass the North Mall Distillery in this period.

This transition took place in a wider context of monopolisation. Excessively onerous regulations would hamper the development of many local distillers. The regulatory burdens ranged from malt taxes on cereals that sought to prevent the supply of raw materials to distilleries, to strict licensing rules around stills and how they were used. These rules, and the speed with which they were frequently changed, resulted in a further impetus towards innovation as businesses tried to sharply pivot in a changing regulatory landscape. Larger businesses were inherently better able to absorb these costs, with the result being that stricter laws produced greater consolidation in the industry, decreasing competition.

With the onward march of the 19th century it was becoming clear that a change in the wider business was needed. The number of Irish distilleries had decreased considerably between 1845 and 1862. Francis Wise thus took the decision to put the North Mall Distillery up for sale, with the following notice from the 9th of August 1867 appearing in the local press:

Mr. Wise withdraws from premises in which an enormous business has been done and an enormous fortune — the largest perhaps in Ireland, and larger than many of the large ones in England — has been accumulated, and the Company of Cork Distillers take his place.

Cork Distillers would be formed from the conglomeration of four of the city’s key distilleries. This would prove an immediate success, allowing the new company to accrue large benefits from economies of scale. Following in the line of previous consolidations, the enlarged enterprise would prove far more resistant to the whims of a changing economy.

It is from this period that whiskey, as a product, begins to take on the character that we would recognise today. Cork Distillers made the key decision to introduce greater ageing of their whiskeys. They would continue selling significant portions of un-aged whiskey directly to merchants, yet by focusing on quality aged products, and building up these stocks, they sought to introduce a new dimension to compete with other producers in Ireland. Cork Distillers would also capitalise on the ‘Wise’ brand by continuing to produce its product at the North Mall under the families name.

Even so, massive restorations and refurbishments were needed at the North Mall to render it operational. The complex was in very poor shape by the time of the takeover, with many buildings beyond saving, necessitating full rebuilds. Much of the equipment would have to be totally replaced. Some £20,000 would be needed to get the facility up to scratch. Even with this investment, the plant was increasingly viewed in a negative light by both the public and Cork Corporation.

The distillery was seen by locals as a hazard to public health, thanks to the massive plumes of smoke rising from the industrial chimneys. Sources from the time claim that the new owners were using three times the amount of coal used by the Wise family and that the coal was of an inferior quality. Chimneys in this time were not the towering structures we tend to associate with industrial activity today. They were much lower to the ground, resulting in more immediate ill effects to the locality.

In the face of other distilleries receiving legal action on the basis of pollution concerns, this created an impetus for the distillery to alleviate these fears. The brick structure, pictured in its reduced state above, stood at a height of 160 feet and cost some £5,000. Extensive works would be required on the wider site to re-route the generated smoke through the new chimney. It is perhaps the only surviving original industrial element to still stand on the site.

Following the sale of the distillery, the Wise family continued to be of significant economic importance to Cork. The Wises had large interests outside of the distillery business, but Francis Wise’s sale of the plant was of huge financial benefit to the family. Whilst the Wise’s had a wider philanthropic legacy, Francis in particular would leave the most enduring mark on the city.

Largely forgotten today, Francis’ support would prove vital in the construction of the new Saint Fin Barre’s Cathedral. As the building had gotten underway, finances for the project had quickly spiralled out of control. Begun in 1865, the money had dried up by 1873, before any of the landmark towers had broke ground. Francis Wise and William Crawford stepped in to save the project.

In addition to the £2,600 he had already donated to the building works, Francis would contribute an additional £20,000 to supplement the further construction. William Crawford would donate some £18,300 in total. At a ceremony on 6th April 1877, commemorating the laying of the top stone on one of the western spires, the bishop would state the following:

We are all entirely indebted for these towers, and for the one which I hope will in due time be completed, to the munificence of Mr. Francis Wise, and of Mr. William Crawford. Properly speaking, this ought to be called the Crawford Tower, as I proposed to Mr. Crawford; but his modesty was equal to his munificence, and he would not let it be called by his name. The other I wish to be called the Wise Tower, because it is owing to the munificence of Mr. Wise that it has been completed.

Francis would go on to make generous donations to various Cork hospitals, including £3,000 to the South Infirmary and £2,000 each to the North Infirmary and Fever Hospital. The scale of his fortune was such that he received the following comment in the Newry Reporter, marking his death in 1882.

[He] lived in an inexpensive and unostentatious manner, and while he was most generous during his lifetime to his relatives and friends, and also gave freely and often munificently to purposes connected with religion and charity, the accumulation of his savings must have been enormous, and it would, therefore, be no wonder that the state of his affairs will prove that he was the richest man in Ireland, and equalled in this respect by only a very few in England or Scotland.

The North Mall Distillery would burn down in 1920. Very little survived the fire, and all operations were transferred to Midleton. The buildings that survived were largely demolished in 1947. A member of the Wise family, then living in Australia, would travel to Cork and give a first-hand account of the remains in October 1950:

The Distillery or a lot of it was burned out many years ago, but the stone all still remains and a huge Chimney stack. The ruins are still there, most of it over-grown with undergrowth, and it seems funny that this valuable land is not put to some use. Many of the old stone buildings of the distillery remain, and with others… are now used as a Bonded store.

The land was put to some use in the 1960s, when a major investment would see a modern bottling plant constructed on the lands of the distillery. The new project would be designed by the Cork modernist architect Frank Murphy and is typically considered his crowning architectural achievement. Such is the affection for the building that University College Cork’s plans to demolish it were scuppered by local opposition. Frank Murphy’s building has been incorporated into the planned redevelopment.

Whilst the history is little known today, the impact of the Wise family on the fabric of 19th century Cork is only eclipsed by that of the Beamish and Crawford families. Ireland’s whiskey production, largely concentrated today at the Midleton Distillery, has witnessed a striking resurgence in the past thirty years. The country has once again become a global player in the whiskey industry. The spirit today forms a core part of Ireland’s international brand. The North Mall Distillery, whilst no longer in existence, played a defining role in the evolution of this history. Through shining a light on its past, it is my hope that we might better understand our present.

This article is heavily indebted to the work of Barry Crocket and Stephen D’Alton via their landmark book Wise’s Irish Whiskey, published by Cork University Press. For those who wish to do more detailed reading, I recommend their book most highly. You can find it: here.

Dare to be Wise — Motto of the Wise family