(darksky.org)

A 2025 global survey revealed widespread satellite interference in astrophotography, with 90% of respondents reporting moderate or worse impacts and 97.5% stating that conditions have significantly worsened over the past five years. This interference carries a substantial burden, costing an average of 27 extra minutes of editing per image, and 78% of participants believe a critical threshold exists, estimated at a median of 25,000 satellites, beyond which astrophotography will be irreparably harmed.

Introduction: The silent invasion in our night sky photos

You’ve seen them: breathtaking photos of the Milky Way arching over a desert landscape. But look closely, and you might notice something out of place—a thin, perfectly straight line cutting through the frame. This is the trail of a satellite, a now-common feature in night sky images. Is this just a minor annoyance for photographers, a digital blemish easily erased? Or is it a sign of a much larger, more fundamental change happening above our heads?

In 2025, DarkSky International conducted a global survey of 203 astrophotographers from 31 countries to find out. The goal was to quantify the real-world impact of the rapidly growing number of satellites on the community most intimately connected to the night sky. The findings don’t just confirm a problem; they paint a startling picture of how quickly our view of the cosmos is being altered.

We reveal the five most surprising and impactful takeaways from this landmark survey—the lived experiences of people on the front lines, documenting a sky that is becoming more crowded by the day.

1. The interference is universal and accelerating

A logical-sounding solution proposed by satellite operators is to dim their spacecraft to below the threshold of naked-eye visibility (around magnitude 7). If we can’t see them, the problem is solved, right?

The survey data, combined with the physics of photography, reveals a major flaw: there is a huge “brightness gap” between what our eyes can see and what a camera sensor captures in the dark.

This gap can be understood with simple comparisons:

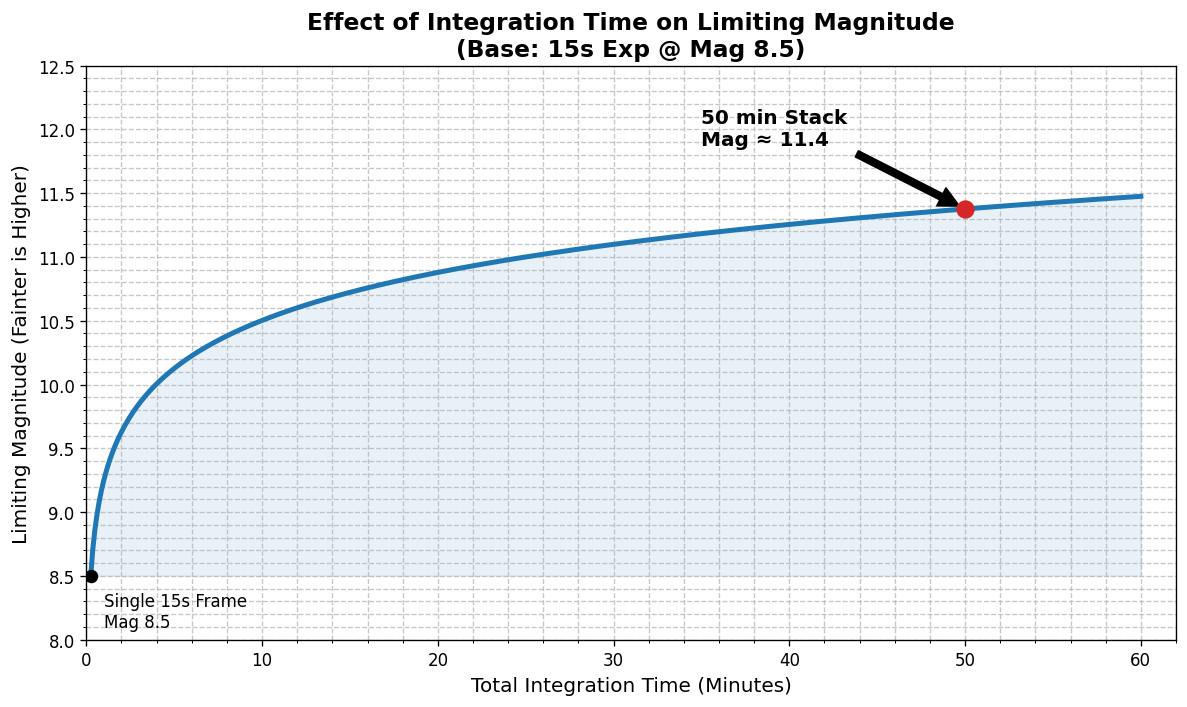

- Nightscape Photo (10-20 sec): This setup can detect objects 6 to 16 times fainter than the human eye. To the camera, a satellite dimmed to magnitude 7 is not invisible; it’s a clearly visible streak, often brighter than many of the stars in the image.

- Deep-Sky Stack: A common technique combining many long exposures can see objects about 100 times fainterthan the eye. Here, a magnitude 7 satellite can be a hundred times brighter than the delicate deep-sky details being captured.

- Telescopic Image: Equipment used by researchers and serious hobbyists can see objects roughly 100,000 times fainter than the eye. From this perspective, a satellite that is completely “invisible” to a human observer can still be tens of thousands of times brighter than the distant galaxies being photographed.

The bottom line is that the terms “invisible to human observers” and “negligible in long astrophotographic exposures” are separated by factors of thousands in brightness. Dimming satellites is necessary, but for the astrophotographer, it is a functionally incomplete solution.

3. The hidden “pollution tax” on time and data

Dealing with satellite trails isn’t just a minor post-processing step; it imposes a real, measurable “pollution tax” on photographers in the form of time, effort, and lost data. This hidden labor is significant:

- Lost Time: Photographers spend an extra 27 minutes of post-processing time per image specifically to mitigate the effects of satellite trails.

- Lost Data: An average of 16 frames are lost per imaging session—discarded entirely because they are too spoiled by satellite trails to be usable.

This mounting cost means that for every hour of successful imaging, a photographer might spend an equivalent amount of time just fighting back the encroaching satellite trails.Worryingly, a plurality of the community (41%) believes that software mitigation techniques (like Photoshop or PixInsight) are not keeping pace with the increasing number of satellites, while only 20% feel they are. This technical challenge is adding deep frustration, as one respondent noted:

- The human eye: Under the darkest skies, the human eye can see stars down to Magnitude 6 or 7.

- Tracked wide-field astrophotography: A standard setup for capturing the Milky Way can routinely detect objects down to Magnitude 11-12. This is approximately 100 times more sensitive than the human eye.

- Telescopic deep-sky imaging: An amateur telescope setup for imaging faint galaxies and nebulae can detect objects down to Magnitude 18-20. This is approximately 100,000 times more sensitive than the human eye.

“It makes it frustrating and distracts from my planned observing and studying for the session.”

4. The community believes a “break point” is imminent

Is there a tipping point—a moment when the sheer number of satellites makes astrophotography as we know it irreparably harmed or even impossible? The community overwhelmingly believes so.

The survey found that 78% of respondents believe such a numerical threshold, or “break point,” exists. When asked to estimate what that number might be, their answers provided a stark warning. The median estimate for this tipping point is approximately 25,000 satellites.

To put this number in context: prior to the first major Starlink launch in May 2019, there were about 4,000 functional satellites in orbit. With planned launches from multiple companies, that total could swell to 100,000 or more in the coming years. This isn’t a distant hypothetical; it is a critical threshold the community sees on the immediate horizon.

5. Beyond pixels: The cultural and emotional toll

Beyond the lost data, corrupted pixels, and hours spent editing, the survey reveals a deep emotional and cultural toll. For many, the night sky is a source of awe, connection, and heritage. The proliferation of artificial objects is seen as a desecration of this last natural frontier.

One of the most poignant stories shared in the survey captures this sense of cultural loss:

“I hate telling my young nieces that what they saw wasn’t a shooting star, so I watch them wish on satellites.”

This sense of loss is actively discouraging participation. The survey found that 22% of respondents said the increasing number of satellites has discouraged them from even going out to shoot. As one photographer eloquently put it, the sentiment is one of profound grief:

“The sky was the last wilderness we had and it’s now ruined.”

Conclusion: A sky full of questions and a path forward

The findings from this global survey are a clear signal from the astrophotography community: the problem of satellite interference is not a future concern—it is here now. It is widespread, rapidly worsening, and technically far more complex than it appears on the surface.

The consensus that we are approaching a “break point” of around 25,000 satellites should serve as a wake-up call, a warning from the people documenting our changing sky that we are running out of time.

To preserve this shared heritage for future generations, action must focus on four core proposals:

- Establish international brightness standards for satellites. Regulations must move beyond the naked-eye limit (magnitude 6-7) and be based on the significantly greater sensitivity of digital sensors, ensuring satellites are faint enough to avoid detection in typical long-exposure images.

- Mandate accountability and mitigation in licensing. Regulatory bodies must treat orbital brightness as a form of environmental pollution. Licensing must be contingent upon operators submitting binding impact assessments and mitigation plans that place the responsibility for trail reduction on the companies creating the interference.

- Foster collaborative development of mitigation tools. Policy should create frameworks or incentives for satellite operators to collaborate directly with the astronomy community and software developers. This will drive the creation of effective, automated, and publicly available mitigation solutions.

- Promote public awareness and education. We recommend supporting educational initiatives to raise widespread public awareness of the value of dark skies and the growing problem of satellite pollution, which is currently a barrier to policy change.

As our orbit becomes another layer of human infrastructure, it leaves us with a profound question to ponder: How do we balance technological progress with preserving our oldest shared heritage—a clear and unobstructed view of the universe? The survey data shows that the answer requires decisive action, and it is needed now.

The policy brief and survey results are available for download.