(reeserichardson.blog)

Almost one year on from Larry Richardson becoming Google Scholar’s highest cited cat, a year and change after Ibrahim et al. released a pre-print (now published) showing that Google Scholar is eminently manipulable and a full 15 years after fictitious personality Ike Antkare became one of the most highly-cited scientists of all time, Google Scholar still appears to have done absolutely nothing to curb citation manipulation on its platform. This is especially concerning given that Scholar is probably the single most commonly-used source for citation metrics used in hiring decisions (according to Ibrahim et al.). Here, I’ll detail a recent citation-selling scheme that exploits Scholar’s longstanding vulnerabilities.

Discovering another citations-for-sale scheme

A few days ago, I woke up to a notification from a WhatsApp group that I had joined where paper mill products and academic reputation manipulation services are advertised. Here, the provider offered to boost the buyer’s h-index on Google Scholar with 100 citations for 300 USD (a 50 USD discount).

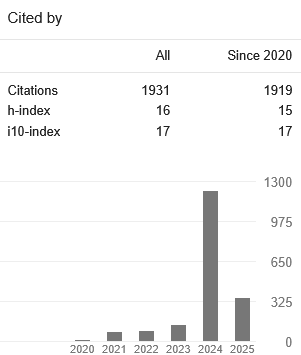

The message links to the profile of an apparent client who, according to Google Scholar, earned 135 citations in 2023 but 1,223 citations in 2024.

Among the citations to the highest-cited articles on this profile, you can find a spate of irrelevant citations from articles in Web of Science-indexed journals published by all of the largest American and European publishers (check out these examples from Elsevier, Wiley, Springer Nature, and Taylor and Francis). However, many of the other papers citing the client’s articles were not from well-known publishers and were instead indexed in Google Scholar through PhilPapers, an online literature aggregator for philosophy.

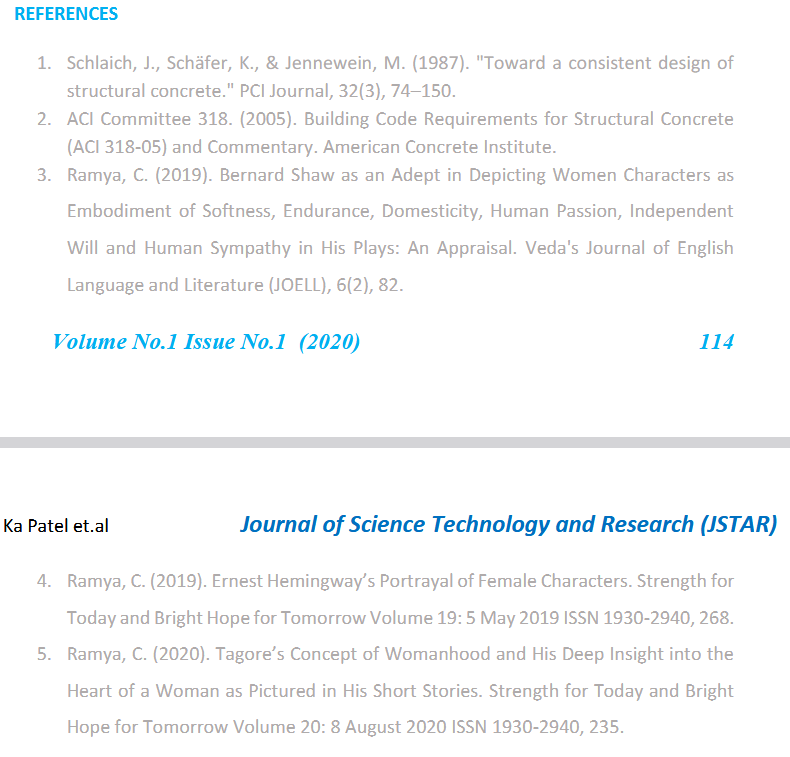

Other articles published by these journals have no in-text citations but list 100+ articles in their bibliography. Many of these bibliographies are filled with laughably irrelevant articles. Consider “Comparative Analysis of Pile Cap Design Using Strut-and-Tie Method (ACI 318-2005) and Conventional Methods”, which cites an unusual amount of literary criticism.

To better understand the scope of this operation, I downloaded every article hosted by JSTAR and IJEIMS. The journals’ websites make it appear like this would be 1,144 articles in total, but many of these are duplicates. As of May 5, 2025, JSTAR hosts 181 unique articles and IJEIMS hosts 204 unique articles. For reasons that are not presently clear to me, these numbers do not exactly match the numbers of articles from these journals currently indexed on PhilPapers (311 and 205, respectively). Both websites are still actively posting new articles: between April 23, 2025 (the first time I downloaded articles) and May 5, 2025, JSTAR and IJEIMS posted 13 new articles each.

I did my best (read: I wrote some exceedingly rudimentary regex code) to extract the references from each article’s PDF. I grouped together the extracted references based on exact string matches. As a result, any references that point to the same article but are formatted differently would appear to be towards different articles. According to this cursory analysis (take note of my lack of precision in reporting these results):

- The median bibliography is around 80 references long.

- Around 3,000 references appear in multiple documents.

- Around 150 references appear in documents from both journals.

- Of these 150, at least half are to articles appearing in journals other than JSTAR and IJEIMS, including articles published by Elsevier and Springer Nature and around 30 articles published by IEEE.

It would take a far more thorough analysis to reduce the gargantuan uncertainty in this estimate, but the number of references found among multiple articles and the frequent reappearance of certain authors in these reference lists make it clear that this operation has served dozens of clients, if not hundreds.

I don’t currently have the bandwidth to perform this analysis myself so I’ve made all of this data (i.e., the complete archives that I downloaded, the metadata for these archives and the references I extracted) available on Zenodo. I hope you consider diving into this dataset yourself. If you fancy yourself a post-publication peer reviewer, consider perusing the reference lists for articles that have likely attracted dozens of bought-and-sold citations in peer-reviewed outlets.

Why fighting citation manipulation matters

It’s easy to become fixated on only the most absurd cases of scientific and academic fraud. It’s also easy to dismiss certain instances of scientific and academic fraud as trivial or otherwise not worth stirring over. However, even the most trivial cases often betray a massive market for scientific fraud and academic reputation manipulation services. This market thrives on and perpetuates inequality in the scientific enterprise. It is a threat to scientists everywhere if the scientists most likely to succeed are those that are able to pay to obtain the markers of success.

Google’s role

The last time citation manipulation on Google Scholar made it into the news (following the escapades of Larry the cat, no less), Google offered no comment to the press on the matter. They removed Larry’s citations within a week but still have not removed any of the citations from fake papers we showed to have been purchased a year ago. If Google wants to demonstrate that it’s not interested in enabling academic fraud with its services, Google Scholar’s developers should at least publicly acknowledge the problem. If they were actually serious about the integrity of their product, they would remove citation metrics from users’ profiles and from subject expertise pages altogether.

Google’s business revolves around acting as the primary conduit through which the masses access information, yet it is has abdicated its responsibilities in maintaining the quality of that access. This is not unique to Google Scholar; the standard Google Search service has also been rotting.

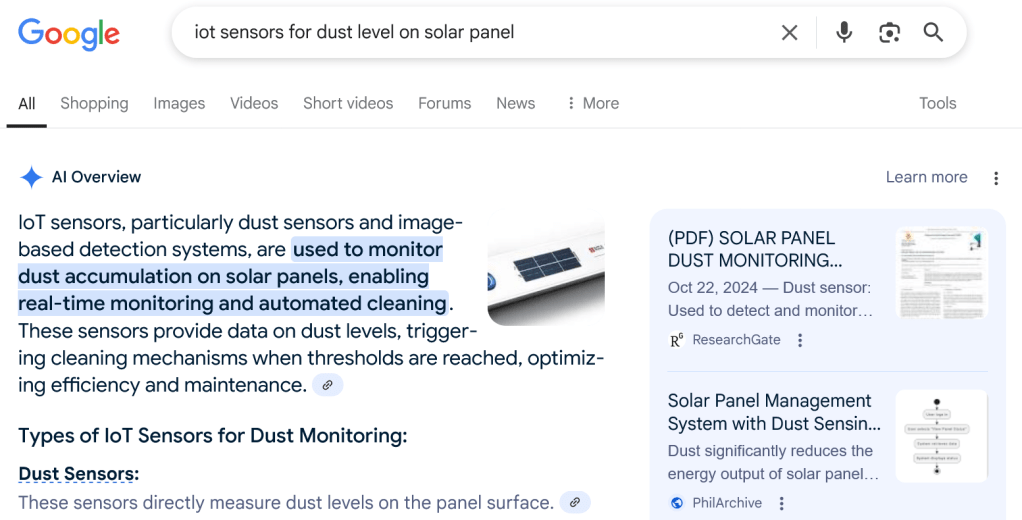

Incidentally, Google’s now-ubiquitous “AI Overview” feature cites information from fake articles hosted by JSTAR and IJEIMS.

While Google clamors to maintain its monopoly on internet search, more scrupulous and accountable curators of information are in the crosshairs of the authoritarians Google has tried to woo:

- Entire staff at federal agency that funds libraries and museums put on leave (March 31, 2025)

- Researchers from China and five other ‘countries of concern’ barred from NIH databases (April 10, 2025)

- Trump’s team, often accused of spreading misinformation, slashes misinformation research (April 30, 2025)

- Citing N.I.H. Cuts, a Top Science Journal Stops Accepting Submissions (April 29, 2025)

- Scientists globally are racing to save vital health databases taken down amid Trump chaos (February 7, 2025)

- US Justice Department cuts database tracking federal police misconduct (February 20, 2025)

- STAT is backing up and monitoring CDC data in real time: See what’s changing (April 29, 2025)

The persistent deficiencies in for-profit literature aggregators like Google Scholar and the growing instability of publicly-funded information curators should remind scientists that high-quality access to information is no guarantee. We should strive to defend the integrity of the information that is out there and the means by which we access that information whenever possible—information that goes undefended does not stick around.

[ UPDATE: May 12, 2025 ]

PhilPapers has informed me that they have removed all articles from JSTAR and IJEIMS from their site. Kudos to the PhilPapers team for taking action (and caring about the integrity of their service)!