(open.substack.com)

I dreamt there was an excavation in my garden.

A flowerbed I knew to be overgrown appeared as a bare brown heap.

A silver shimmer of affordance passed across it.

Something, waiting.

Press X to interact.

I know something is buried there, and the soil is trembling.

Around me, workmen laugh, too loud, too constant, spilling into everything until it is hard to tell if the sound comes from them, from me, or from the ground.

In the churned dirt, bugs crawl across the surface, their bodies smeared flat textures, sliding endlessly over one another.

For the past five years I’ve been circling one question: how do we perform, and how do we play, in the drift of daily life? Over the last year the question has turned toward the baroque—or more precisely, the neo-baroque. Did the baroque ever end, tied to a single historical moment, or has it continued to mutate, surfacing in new forms when culture grows unstable? I’ve come to think of it less as a style than as a recurring dynamic, a way in which excess presses at the edges of the present.

My argument is, in the 2020s, it has returned not through marble altarpieces or gilded ceilings, though one could be forgiven for thinking so given the en-goldening of the white house, or Carrie Johnson’s rather overwhelming renovation of Downing Street, but instead through the jittering energies of digital aesthetics. One of the strangest and most pertinent examples of this is Fat Dog, the London band whose manic live shows stitch together rave kinetics, absurdist humour, klezmer scales and an unabashed embrace of chaos.

When asked by Rolling Stone what genre they belong to keyboardist Chris replied: “I always just say it sounds like rabbis on ecstasy.” With frontman Joe following up bluntly: “You listen to stuff and you put pieces together, and you steal a lot of shit: stealing is a massive part of it. If you steal 13 songs in one song, then no-one can realise.”

While the rhetoric of theft is not new to music, the inclusion of a type of excess resonates precisely with what Angela Ndalianis, in her work on video games like Serious Sam and Duke Nukem, identified as the neo-baroque: a mode of cultural production defined by spectacle, sensory overload and an irreverent recycling of forms (Ndalianis, 2004). The baroque, in this reading, is less about refinement than about proliferation — an art of abundance and instability.

It is no accident that Fat Dog’s klezmer melodies came, as Joe admits, not from some deep connection to a musical tradition but from Serious Sam 2: “I just played [it] a lot, where you’re in the pyramids and you’re shooting loads of tentacle aliens, and I was listening to the soundtrack from that. I use the same scale in all my songs.” What was once a digital background noise of their youth has now been elevated to the spine of their sound.

Serious Sam, like Duke Nukem, exemplified Ndalianis’ sense of the neo-baroque: a delirious architecture of abundance which echoes the ceiling frescos of Bernini or Borromini’s impossible curves. These games overwhelm players with endless enemies, explosion and gaudy ornamentation, until perception itself became unstable. And it is precisely this aesthetic of too much that Fat Dog have resurrected for a generation saturated with irony and yet who hunger for intensity.

Yet, before I go on I want to turn to the matter and layer of production. Their debut album WOOF is produced by James Ford, the long-time Domino Records figure whose hand has shaped the baroque excess of British rock for nearly two decades, with artists including the likes of The Last Dinner Party, The Last Shadow Puppets and The Last Arctic Monkeys.

With Arctic Monkeys, Ford’s production steered their sound away from wiry guitar riffs and towards lush orchestrations and a type of cinematic scope I’ve rarely heard in any other artist. The Car (2022), in particular, is a sonic soundscape of grandiose strings that evoke the sweeping view of post-war cinema in the vein of Fellini or Hitchcock, each track on the album swelling like a film score, ornamented in such a manner that evokes 8 1/2 more so than it does their origins in the Sheffield garage rock scene. Similarly, with The Last Shadow Puppets’ second album, Everything You’ve Come to Expect (2016), Ford amplified Alex Turner and Miles Kane’s embrace of orchestral drama and theatrical camp. These are not simply retro gestures, they were postmodern baroque revivals, swirling with decadence and spectacle.

Through Ford, Fat Dog inherit this baroque lineage. Yet where Turner’s baroque leaned in a languid and crooning form of velvet decadence, Fat Dog’s iteration is feral, digital and chaotic. Their baroque does not unfurl in cinematic strings but klezmer scales ripped from Serious Sam 2; there’s no place for the widescreen melancholy here, only breakneck tempo, distortion and mosh-pit ritual. Still, the connection is clear: Domino’s catalogue charts a trajectory of neo-baroque aesthetics in British music.

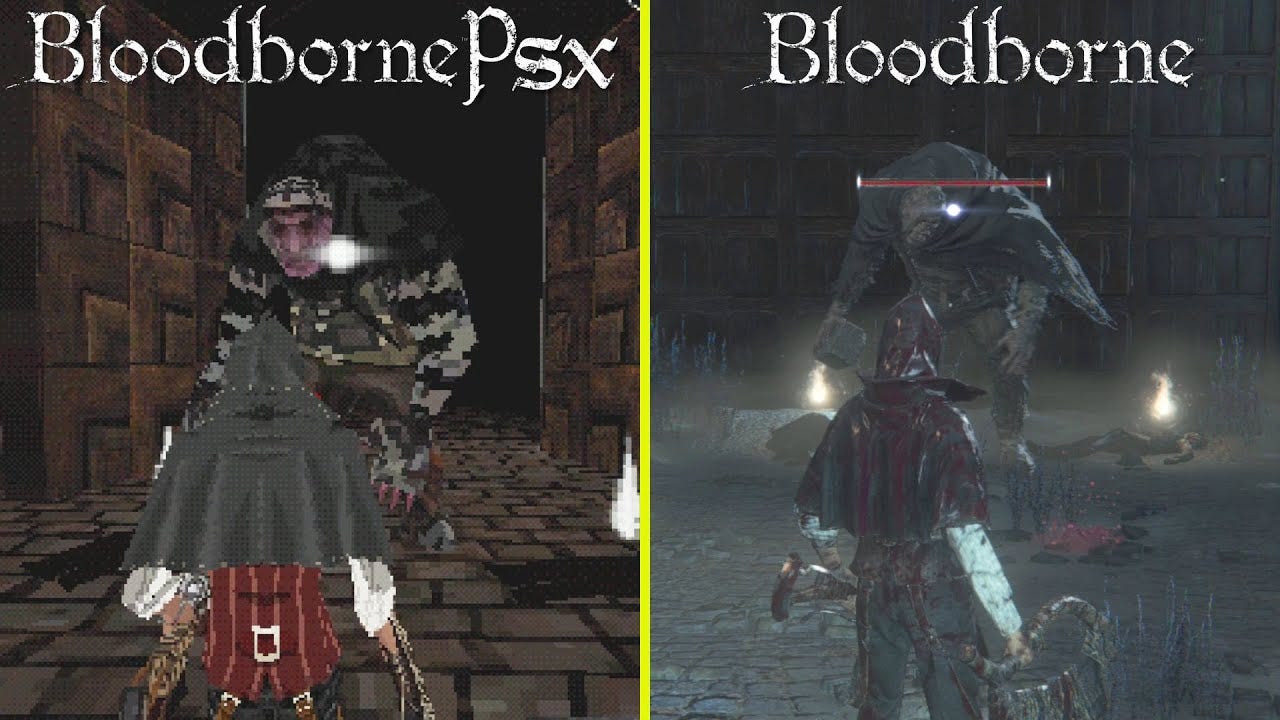

What makes Fat Dog distinct is the way in which this baroque lineage is filtered through a type of digital ornamentation. Their videos lean into PSX-era aesthetics: low-poly models, jagged textures, a visual language of glitch parody and awkward floating point rendering. If The Car offers baroque in the key of strings and sweeping camera pans, Fat Dog’s visual world reimagines the baroque through the maximalism of early 3D graphics, with ornaments that flicker, stutter and fracture into pixels.

Before returning to Ndalianis, it’s worth pausing to explain what the PSX aesthetic means for the uninitiated. PSX typically refers—though the term has grown loose in practice—to digital assets that deliberately recreate the look of 1990s and early 2000s graphics. Polygons, the basic building blocks of 3D models, were then limited to the dozens or hundreds, compared to the tens of thousands now used for a single detail (I recall a design talk in which the developers of Tomb Raider boasted of taking Lara Croft’s breast from fewer than ten polygons to many thousands—a somewhat vile anecdote, but illustrative nonetheless). Compressed photographic textures plastered onto flat planes, producing an uncanny effect: the look of a real body projected onto cardboard. While animations were limited to appearing at fixed whole-number points within the games geometries (a unique quirk of the PlayStation 1), giving the appearance of models rippling and oscillating as decimal positions are rounded with each draw of the screen.

This is what matters for Ndalianis. Writing during the very era the PSX aesthetic recalls, she argued that the neo-baroque thrives in media that overwhelms perception through multiplicity, spectacle, and excess. The awkward polygons and surreal geometries of PSX graphics were already baroque in their refusal of naturalism. Fat Dog seize on this history, reviving low-poly ornament not as nostalgia but as a digital grotesque, the visual analogue to their klezmer-punk avalanches.

I felt this baroque logic first-hand at Shambala. At the prompting of a friend we both began to open a circle in the crowd, pulling smaller pits into a single great orbit. As the break for King of the Slugs began, dancers hurled themselves inward, then outward, then around, knees lifted, arms flailing, bodies colliding. It was less like a mosh pit than a rite: a circle dance pitched somewhere between punk violence and folk procession.

But it also felt unmistakably digital. The jagged momentum of the pit, each body shunting in abrupt angles, recalled avatars in a PSX brawler: polygonal, exaggerated, always on the verge of breaking apart. In the blur of strobe and distortion, the pit became a living low-poly simulation: edges colliding, surfaces clipping, bodies reduced to rhythm and velocity. What should have been chaotic was, strangely, ornamental, a ritualised glitch staging the very excess the music demanded.

What struck me most, though, was the mix of bodies in motion. Ravers, punks, kink pups, festival drifters, all swept into the same rhythm, distinctions blurred by the sheer force of excess. This is what baroque media does: it does not refine or separate, it gathers. The pit became a living ornament, a space where identity was less about category than about participation, each body folded into the same spiralling excess.

As Ndalianis reminds us, the baroque spectacle always threatens to overflow its frame, pulling the spectator into its orbit until stage and audience collapse into one. Fat Dog’s shows enact precisely this collapse: the pit isn’t “beside” the performance, it “is” the performance, a playful act of co-creation and a sensory torrent that refuses to stay contained. What matters isn’t coherence but virtuosity — a tour de force of excess of klezmer scales, rave drops and stolen fragments. Omar Calabrese once described the neo-baroque as a culture of limits stretched to breaking, a condition of perennial suspension. It is in this state that Fat Dog thrive. Their gigs don’t promise transcendence or revolution; they hold the crowd in a storm of excess itself. In that storm, ravers, punks, pups, pingers and wanderers are gathered into a single ornamental field, each identity flattened and recomposed in the overwhelming shimmer of noise and movement.

This mixture of slapstick, ritual and maximalism is recognisably baroque in Ndalianis’ sense of the term. If the baroque of the Counter-Reformation sought to overwhelm the senses in a bid to reaffirm faith, then Fat Dog’s baroque overwhelms the senses in an attempt to ward off the algorithmic flatness of our contemporary culture. Their concerts feel like games gone feral: music as spectacle, bodies as avatars, each movement spiralling outward rather than resolving inward.

The band may joke about being “incel Viking choirs” or “rabbis on ecstasy,” but these masks, like the latex dog face, are precisely the point. They are ornaments in motion, gestures of excess that refuses containment.

In this light, Fat Dog are not simply another hype band. They are conduits for a longer cultural logic: the re-emergence of the baroque from digital aesthetics. What once seemed to be confined to the experience of my childhood and the worlds of Serious Sam and Duke Nukem has leaked outward into music, stagecraft and collective experience. To attend a Fat Dog show is to find yourself inside the digital baroque, not on a screen but in a crush of bodies slugging it out together.

It is important to consider where this trend arises, or more importantly how it can differentiate itself from the movements that precede it. I mentioned that Fat Dog steal, but this is not unique to them, so how then does their work stand apart from the past 30? 40? years of music production?

Let’s look for a moment before we conclude to the digital aesthetics of the 2000s, and for those of you that want to know more, I will point you to Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life. Then, the dominant mood was hauntological: albums by artists such as Asher, Burial, or Position Normal built their atmospheres from vinyl crackle, tape hiss and half-erased voices. Crackle was a sonic allegory for loss, reminding us of the vanished media forms, fragile analogue materiality and the entropy of memory itself. Those sounds drew listeners into a world of ghosts and absences, where the past pressed faintly against the present.

Fat Dog’s baroque is the inverse. Where hauntology made absence audible, Fat Dog insists on presence and a saturation of sounds. Where crackles once signalled loss, they now conjure plentitude. Their aesthetic captured not by analogue grain but by digital polygons — jagged, excessive and overwhelming. Theirs is not the entropy of fading tapes, but the chaos of too many inputs at once: 13 stolen songs colliding in a single track, klezmer scales resurrected from a forgotten FPS soundtrack, dog masks and slug chants erupting in crowded venues.

If the 2000s gave us the sound of things slipping away, the 2020s give us both the sight and sound of things piling up. Fat Dog stand at the front of that pile, proof that the baroque has once again mutated, this time through the digital excess of games, memes, polygons and live performance: a delirious cultural logic for our moment.

Here, my thoughts return, as they often do to Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History:that strange figure of Klee’s who looks backward, seeing one single catastrophe piling wreckage upon wreckage on her feet, while s storm from Paradise propels her into the future. Benjamin tells us the angel cannot unfold her wings; she is held in place by the storm. Calabrese would call this a state of perennial suspension where limits are stretched but never resolved. Yet in Fat Dog’s universe, suspension becomes motion: the angel has learned to skank. She does not resist the gale, arrest time or try to escape the wreckage. She moves within it, knees lifted in crooked time, embracing the storm as rhythm. What was once paralysis becomes motion, what was once ruin becomes texture. The angel has not escaped catastrophe — she has made it dance.