(open.substack.com)

I dedicate this essay to Ines Jurado, who struggled to secure dignified housing while raising a family, as many mothers do. After she passed, their landlord of 12 years evicted her children— I had just befriended her daughter weeks before. I write in the service of women like her because I am inspired by women like her. Happy Birthday Mrs. Isabel’s Mom <3

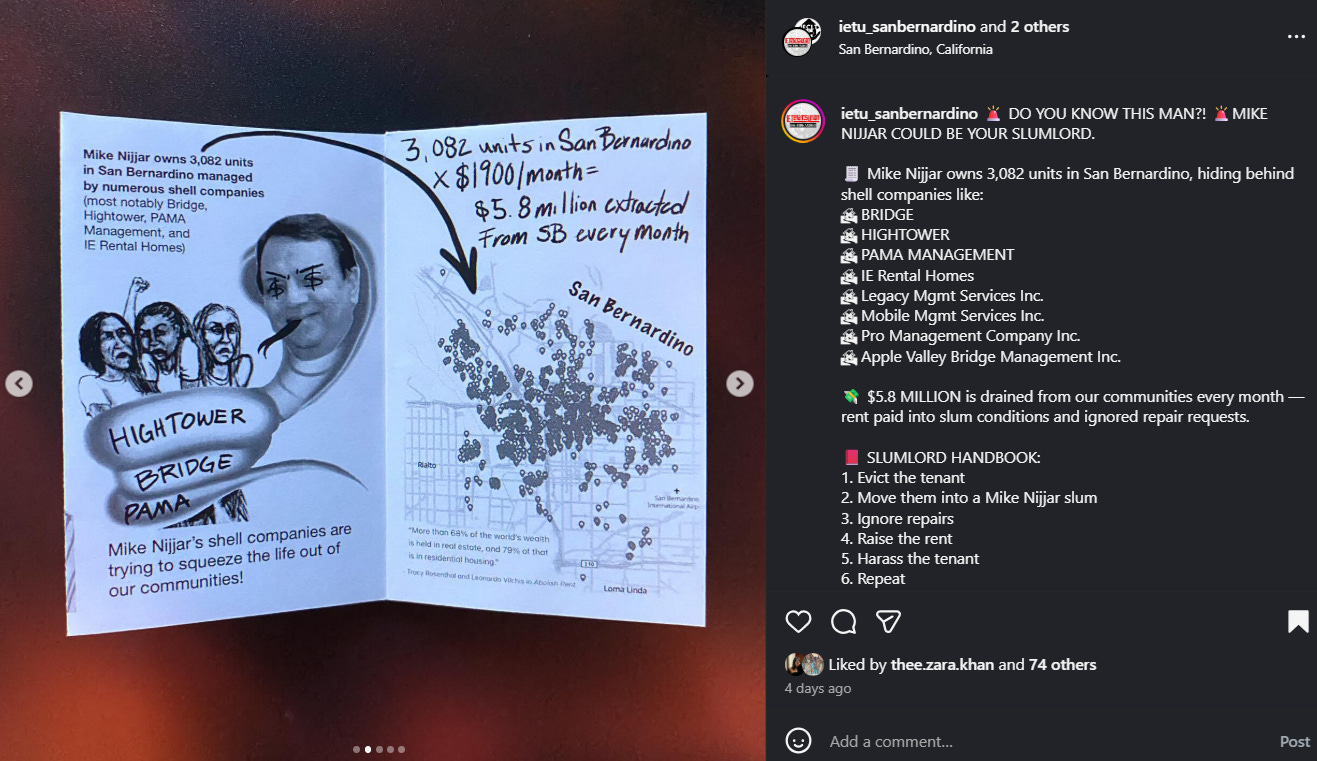

On Saturday, July 26th, the Inland Empire Tenants Union (IETU) hosted a press conference and rally to protest Mike Nijjar’s monopoly over housing in Southern California. In solidarity with the Inland Equity Community Land Trust and the Inland Empire Reading Group for Political Education, the event was held across the street from Hightower Management’s office in San Bernardino.

Hightower, along with PAMA, Bridge, and IE Rental Homes, was publicly condemned by the protestors, but they are only a few of Nijjar’s many subsidiaries that exploit working-class renters (some of which are listed in the audio recording at the top of this article). According to a 2020 LAist article, Nijjar controls the well-being of tenants in 16,000 properties in San Bernardino County, Riverside County, Los Angeles County, and Kern County, among other regions. Nijjar’s wealth is estimated to total $1.3 billion in real estate alone, while his typical renter lives paycheck to paycheck, at risk of being evicted.

Although there is much to be said about the financial scandal that is Nijjar’s empire, the overlooked but obvious truth is that housing insecurity costs the average American their right to a dignified life and their personal agency.

It cannot be argued that housing isn’t necessary for a dignified life. Having a stable home impacts health, employment, access to social services, and even social standing. The adequacy of the home also impacts self-worth, safety, finances, culture, and many other details that make up a life. Simply put, your environment is a reflection of you.

In 1948, the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognized that housing is a human right in Article 25–

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.”

As if common sense needs a legal precedent, other documents, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child, also enshrine the connection of this basic right to a dignified living. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), for example, does so in Article 11–

“The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions.”

Interestingly, the US has not ratified the ICESCR and isn’t compelled by international law to guarantee that its citizens are housed. To that point, there are no admittances under any federal law that guarantee Americans are entitled to housing. Instead, The Fair Housing Act, or “Title VIII” of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, simply safeguards protected classes from being discriminated against in their pursuit of housing. However, in a unique instance, in 2011, Madison County in Wisconsin adopted a resolution that confirms housing is a human right and references the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as well as the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in its reasoning. In 2021, in a failed but substantial instance, House representatives Pramila Jayapal (WA-07) and Grace Meng (NY-06) attempted to pass the Housing is a Human Right Act, which would have “authorize[d] more than $300 billion for crucial housing infrastructure while reducing homelessness across America.” Of course, capitalist systems benefit from housing being a commodity rather than a human right. Fortunately, countries are transitioning to wellbeing-based systems of governance that center dignified living instead of economic systems.

The office of the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing established a frequently cited, 7-point criteria that clarifies the minimum standards for “adequate housing”:

tenure over housing that prevents eviction

housing must supply basic services (water, energy, sanitation, storage, and disposal)

housing must be affordable

housing must be physically habitable and protect from hazards

housing must be accessible for protected classes

housing must be in a reasonable location with access to other human rights (employment, education, medical services, community, and other social centers like childcare)

housing must be culturally competent

The office also identifies local governments as the primary responsible guarantors of dignified housing. This is because local governments “tend to be assigned responsibilities for provision and management of services such as water, sanitation, electricity and other infrastructure; land-use planning, zoning and development, which relates to decisions regarding evictions, displacement and relocation; implementing programmes to upgrade informal settlements and inadequate housing; enforcing health, safety, environmental and building standards; providing local emergency shelter; putting in place or implementing disaster risk reduction and response policies; and regulating the use of public space.”

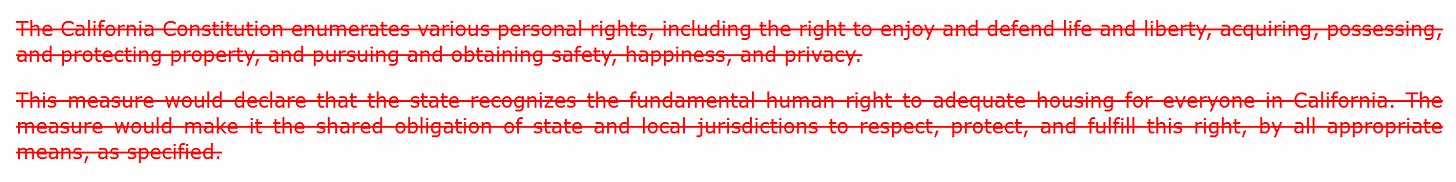

In California, housing is not recognized as a human right, yet. In 2020, under the pretense of cost and duplicate efforts, Gavin Newsom rejected AB 2405, in which the state would have formally recognized that housing is a human right and required it to eradicate homelessness. In 2021, Darrell Steinberg, a former mayor of Sacramento, proposed an ordinance that would require the city to build enough shelter for its homeless population by 2023, but critics resented that it didn’t specify permanent housing. In its original language, the 2023 Assembly Constitutional Amendment 10 would have affirmed that housing is a right of all Californians and required local governments to house their communities. This amendment was heavily supported by social justice advocates, but opponents were concerned that it’s costly, vague, and could complicate legal proceedings. Although it did become codified last June as Res. Chapter 134, Statutes of 2024, any affirmation that housing is a human right was stricken from the text. Instead, it generally reaffirms that local governments must address the housing crisis through typical mechanisms. More recently, this June, a State Senator proposed that Sacramento county coalesce its resources to address homelessness, rather than each city within the county attempting to address the task itself. Although it could simplify certain aspects of the financing and construction process, it does little to resolve housing insecurity or the state’s supposed lack of funds.

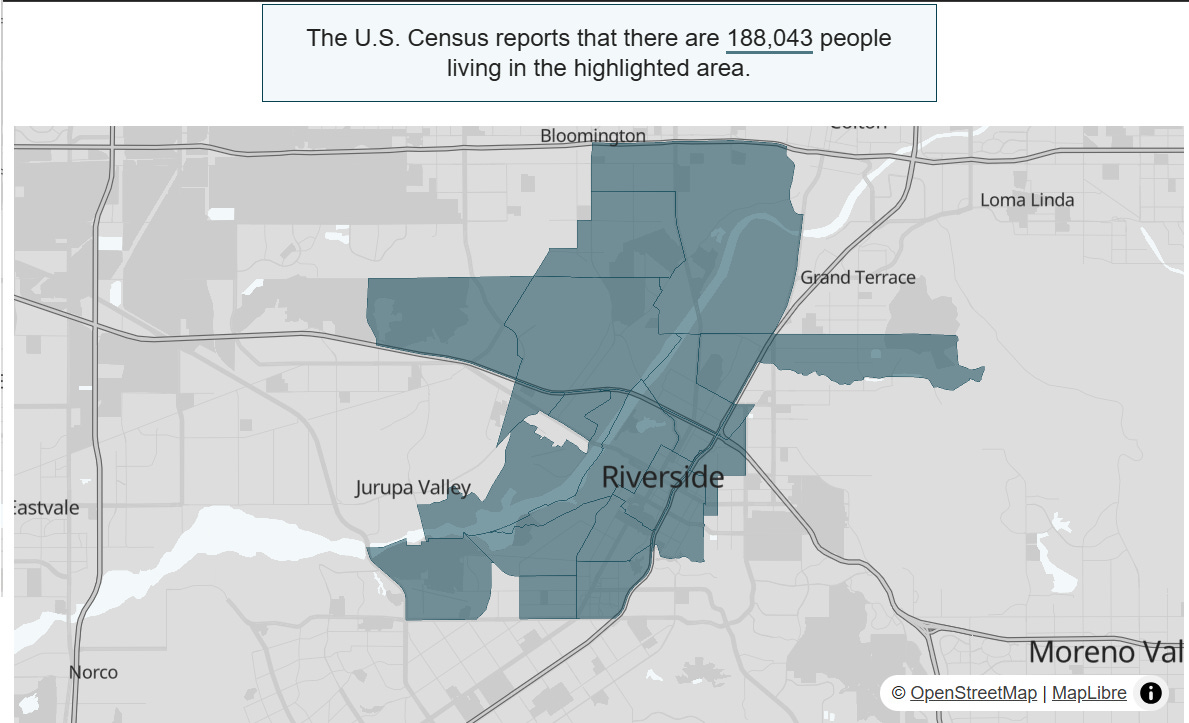

Data from the 2024 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress estimates that 187,000 Californians are homeless, 127,000 of which are unsheltered. Being unsheltered means they are homeless and residing in places that are not deemed habitable, such as underpasses or parks. Unfortunately, it is unclear how many members of this population are specifically children within a family but the report suggests homelessness affects about 26,000 family members. What’s more, the report estimates that 9,000 of the 187,000 are minors without a family. For context, there are ~319,000 people living in Riverside– imagine that 59% of our population was homeless.

Especially considering that climate change, natural disasters, economic inequality, and armed conflict are increasingly plaguing our communities, it is more important than ever that our local and regional governments recognize housing is a human right and take immediate action to house every Californian.

The IE Tenants Union formed in response to these troubling facts and the very real evidence that such matters do affect our community. Speakers at Saturday’s rally shared stories about neighbors who have been evicted or lost their homes in fires that would have been prevented with proper code enforcement, as well frustrations about safety in neighborhoods with high crime rates and health concerns about living in pest-ridden units. Examples such as these and the increasing cost of rent inspired IETU’s targeted opposition to Mike Nijjar and his monopoly over housing in Southern California. Their union seeks to address the housing crisis by empowering tenants to form mutual aid networks and safeguard their right to dignified living. They are also doing their part to push for a rent-free world by advocating for laws that improve housing security and by constructing affordable homes in Adelanto.

You can join their union, which has chapters in Riverside, Redlands, San Bernardino, Hemet, Perris, the High Desert, San Jacinto, and Indio. Or you can create your own.

A tenants union is a group of people with shared interest in their occupation of a building, neighborhood, or other local territory. Specifically composed of renters, a union is a mutual aid network that offers support in many forms but especially through collective action in response to crisis, such as an eviction or hazardous living conditions. Forming a tenants union is as simple as finding a group of 3+ renters, locating a safe space to gather, agreeing upon your purpose, maintaining frequent meetings with productive agendas, and taking action on your goals. Worth noting is that tenants associations are protected by state law and, therefore, can more easily seek legal assistance for addressing their concerns or achieving broader goals. The Pasadena Tenants Union, for example, grew from 3 organizers in 2016 to an expansive community that succeeded in passing Measure H in 2021. This city ordinance, proposed by the people and for the people, included rent control, just-cause eviction criteria, a rental registry, and tenant-staffed boards for assessing landlord/tenant disputes. Although forming a tenants union is simple, responding to housing crises never is, but there is power in solidarity.

A tenants union’s dual-purpose as a mutual aid network is absolutely invaluable, especially given the worsening political climate. Mutual aid networks are both defense and offense against the patriarchal and capitalist society that weaponizes isolation. In this culture that champions personal success, the individual is encouraged to blame their hardships on their neighbors rather than their government, which supposedly exists to guarantee its citizens a dignified life. Mutual aid networks not only humanize neighbors by fostering relationships, but they also empower members with an expansion of resources. The relationships that are built within a tenants union inevitably extend beyond a simple shared interest in housing– safety, nutrition, pollution, wages, religion, schooling, transportation, and gentrification are some of the many other concerns that unite a community. Collectively, neighbors improve their overall quality of life when everyone contributes their unique strengths within their reasonable means– and yes, people love to be helpful.

Improving our quality of life will improve our society, in a perpetual cycle of positivity.

So far, our cultural expectations for dignified living conditions have been systematically distorted by landlords, like Nijjar, who exploit tenants and even our own government, who is corrupted by lobbyists. Our culturally low expectations for dignified living conditions have extremely negative ramifications– allowing ourselves to be mistreated in homes that we struggle to pay for distorts our personal agency by psychologically threatening our sense of self-worth. Take the example of a “ghetto”-- a space where members of the perceived “lowest” castes are sequestered. Given that a person’s environment shapes their beliefs, appearance, behavior, socialization, choices, and even access to opportunities, it is obvious that an inadequate space instills an inadequate sense of self-worth in the resident, distorting their sense of agency over their life. Many formal studies prove that inadequate housing correlates to other social issues including poor health, functional illiteracy, and unemployment, as does empirical evidence. Especially considering that rent is so high, it is important to shift cultural expectations about dignified living. Of course, this means solidarity within the working class.

Without a doubt, a human’s basic right to a dignified life naturally guarantees a healthy sense of agency over their life, which is a prerequisite for sustaining a peaceful society– our governments need to be guaranteeing our human rights; otherwise, what is their purpose? Adequate housing is a right, not a commodity. We will never achieve a peaceful society if adequate housing is not guaranteed. As long as anyone is oppressed, everyone is oppressed. Saturday’s press conference was another cry of solidarity in a country that is rapidly assessing its citizens quality of life. Join a tenant’s union because it is in your best interest, because there is strength in community, because you deserve to live in dignity with the agency it affords.