(breachmedia.ca)

Canada’s political and media class has spent years chasing convenient villains to blame for the housing crisis, pointing the finger at foreign buyers, immigrants, supply shortages, zoning rules, or an overheated market.

But these diversions obscure the real engine of the disaster: a banking system that has spent decades pumping cheap credit into housing with reckless abandon, inflating a bubble that ensures Canadians, not lenders, will be left holding the bag.

According to a new report by The Shift, an international housing rights organization, Canada’s “Big Six” banks—RBC, TD, BMO, Scotiabank, CIBC, and National Bank—are chiefly responsible for engineering this debt-fuelled bubble. Their lending practices are actively creating the high price of housing, and feeding a national cycle of extreme indebtedness.

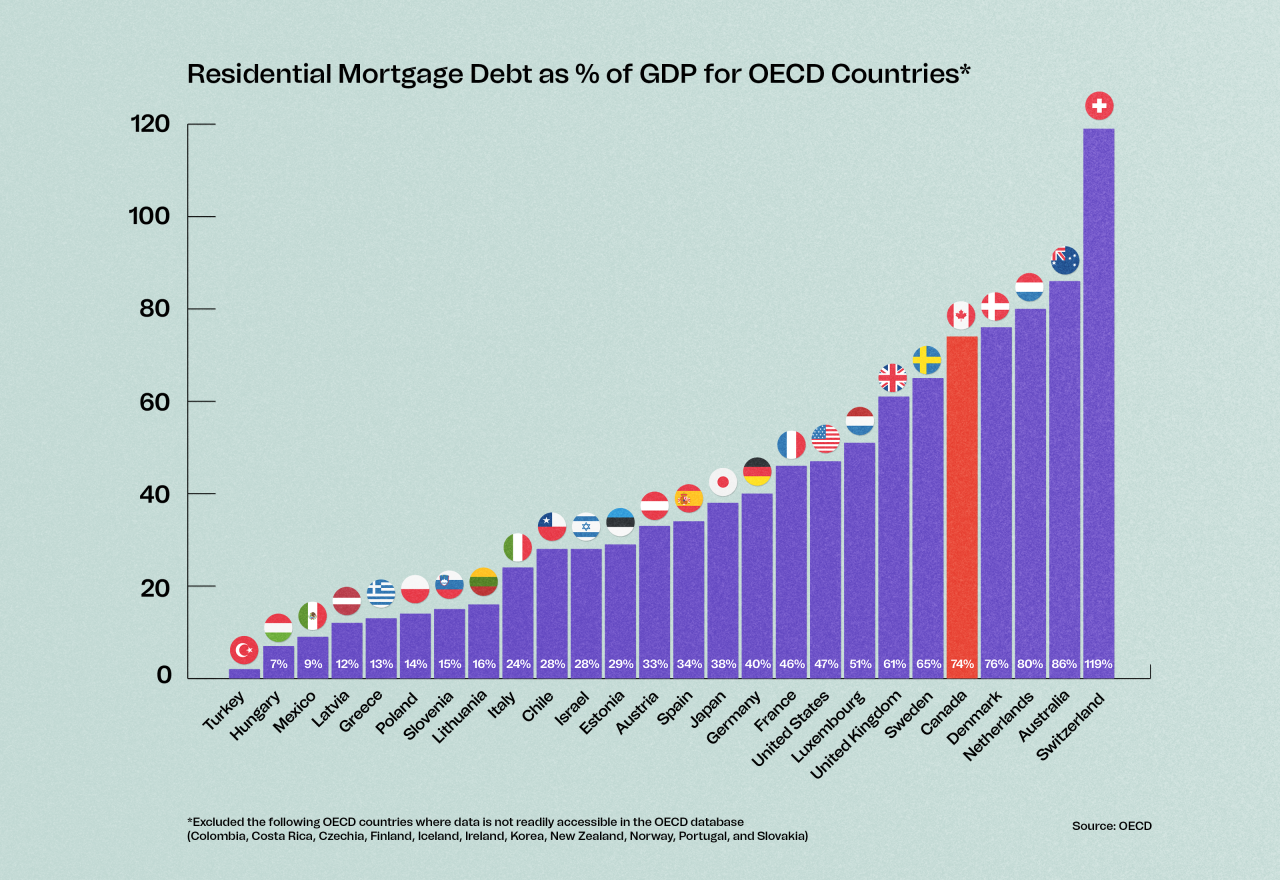

Together, the big banks, which control most Canadian mortgages, made nearly $60 billion in profits last year. At the same time, mortgage debt has ballooned to more than $2 trillion, equal to an astonishing 85 per cent of Canada’s GDP.

Banks drive mortgage debt, inflate home prices, and finance the pushing out of long-time tenants. They do this while earning unprecedented profits and benefiting from government guarantees. Then conveniently, they remain conspicuously absent from most political debates about housing reform.

“When we name banks as culprits, we shift the conversation from ‘housing crisis as inevitable market force’ to ‘housing crisis as the result of specific institutional practices that can be changed,’” Leilani Farha, global director of The Shift and a former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, told The Breach.

“This is about accountability. Banks, like all businesses in Canada, have a responsibility to uphold human rights. And they’re failing to do so.”

Cheap credit goes in, higher prices come out

The central claim of the report, titled Banks and Canada’s Housing Crisis, is that credit expansion is the main reason for skyrocketing home prices, amplifying every other pressure in the system.

Low supply, population growth, investor demand, and zoning regulations all play a role in shaping the housing landscape, but none of them translate into higher house prices unless households can borrow enough money to bid those prices up.

The report puts it this way: “When cauliflower or almonds go up in price because of weather events, most households would forego those products or decrease the amount they purchase. When house prices go up, however, households are told by financial institutions and government policy they can still ‘afford’ the home through the availability [of] low interest loans, or longer amortization periods.” As a result, home prices go up.

Back in 2000, the average Canadian home cost about $225,000. By 2010 it was $340,000, and today it sits above $670,000. That’s an increase of nearly 200 per cent in just a quarter-century.

“Cheap debt creates an upward spiral in home prices,” said Farha. “Banks and government feed this upward spiral further by making it easier to access these bigger mortgages, either by lowering the minimum down payment or extending the amortization period. This is often marketed as affordability, but it’s actually just making it easier for people to take on debt.”

And the political class promises affordability while working with banks to expand mortgage access. Ottawa’s recent decision to raise the price cap for insured mortgages from $1 million to $1.5 million (pitched mainly to first-time home buyers who lack the resources to make the typical 20 per cent down payment, and for whom insurance is needed to protect the lender if the borrower defaults) is poised to inject even more credit into the market.

“When banks make credit cheaper or easier to access, buyers can make bigger, ‘more competitive’ offers, which leads to homes selling ‘above asking price,’” Farha said. “These inflated sale prices then become the new baseline for what similar homes are worth.”

Debt terms for mortgages are typically 25 years—the time it takes to pay it off is called the amortization period. But by 2023, the report notes, around a third of bank mortgages stretched beyond 30 years. Lower monthly payments over a longer time horizon sound appealing, but it means that a typical 30-year mortgage results in a homebuyer paying 21 per cent more total interest than they would on a 25-year mortgage.

So while homeowners take decades to build equity, they are funnelling profits to banks. In 2022, around 32 per cent of mortgage holders were spending more than they earned, and over 65 per cent were struggling to meet financial obligations, up 22 per cent from 2020.

Your mortgage may not even be owned by your bank. Financial institutions routinely bundle mortgages into mortgage-backed securities, sell them to institutional investors, and use the proceeds to issue more loans. In 2023, $503 billion worth of Canadian mortgages was “securitized”—repackaged to be sold to investors—all backed by public guarantees through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC).

This framework, which allows global capital to invest in Canadian housing, turns homeowners into financial instruments. Borrowers still deal with their bank, but their payments go toward servicing investor returns. And because governments guarantee these securities, they’re forced to step in to cover the losses if the value of housing plummets. This has the effect of shifting financial risk from private investors to the public.

Programs like Canada Mortgage Bonds and the expansion of mortgage securitization since the 1990s have made it easier for buyers to take on larger loans, further embedding homeownership as a vehicle for financial accumulation. A report by the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate even explained that securitization has “driven high increases in home prices that are pushing homeownership beyond affordability for more and more people.”

Financing displacement in the rental sector

The report shows that banks play a major role in the rental crisis, yet the depth of their influence is rarely acknowledged by the media, mainstream economists, or the real estate insiders whom news outlets often cite.

When large landlords, developers, or pension funds seek commercial financing to buy apartment buildings, banks evaluate the deals using formulas that reward owners who push rents higher. The most important metric here is what’s called the debt service coverage ratio.

This ratio is calculated by dividing a property’s net operating income—essentially the rent collected minus operating costs—by the annual debt payments on the building. Banks typically require a ratio of at least 1.25, meaning the property must generate 25 per cent more income than needed to cover the mortgage.

This creates a direct imperative for landlords: if rents or fees are too low, or operating costs too high, the property risks falling below the required ratio, which can jeopardize their loan terms. In other words, the report says, the ratio actively pressures landlords to increase rents, minimize spending on maintenance or tenant services, and pursue renovations that boost revenue.

Banks also reward landlords who “reposition” older buildings—industry-speak for renovating units, raising rents, and displacing long-time tenants—by offering better financing terms for refurbished buildings that command higher revenue. The report labels this system “displacement financing.”

Non-profit housing providers, by contrast, are penalized by bank lending criteria: they face lower loan-to-value ratios, higher equity requirements, and shorter amortization periods.

A system built to enrich banks—not households

Decades ago, policies like “asset-based welfare” promoted the notion that rising property values would provide a safety net for middle- and working-class homeowners as the traditional state welfare system was rolled back. Today, Canada has drifted into a paralyzing asset-inflation trap: rising home prices have become at once the financial cornerstone for millions of people and the key factor eroding affordability and distorting investment across the entire economy.

“We’re dealing with an ecosystem here,” Farha said. “Banks, governments, CMHC, and institutional investors are all interconnected, and their goals aren’t always aligned with ensuring adequate, affordable, secure housing for everyone.”

To break this cycle, the report recommends amending Canada’s Bank Act to prevent lending practices that undermine housing rights, including preferential terms for loans that preserve or create affordable units and real penalties for financing that drives evictions or excessive rent hikes. Banks should also reform commercial lending criteria to prioritize tenant security and affordability, restricting loans to landlords with histories of displacement or exploitative rent increases.

Farha further emphasizes that a portion of bank profits should be directed toward funding affordable housing through non-profits, and that gains from CMHC-backed mortgage securities should be reinvested to support public housing initiatives, tenant protections, and acquisition funds that can compete with investor-driven speculation.

“When you’re making $60 billion a year, you can afford to invest in housing as a human right, not just as a profit centre,” she said.

If policymakers are serious about affordability, they need to stop treating banks as neutral actors and start regulating them as what they are: major architects of the crisis.

What are people saying about The Breach?

‘We need an outlet, a source of information that is credible, that is progressive, that we can cling to and believe in’

David Suzuki

Want to support journalism you can believe in? Become a sustainer today.